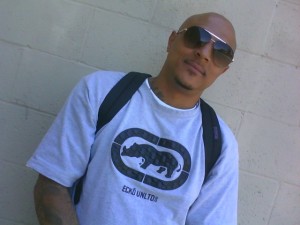

Ex-prisoner Quiano Smith, 31, says he can’t find a job because California’s employers have a “once a convict, always a convict” attitude.

Times are tough, and the majority of the population has to deal with obstacles like foreclosure, unemployment and the high cost of living.

These factors combined can make it particularly hard for the average Californian to get ahead.

Those same obstacles intensify when one is a recently released parolee.

Quiano Smith, 31, is a parolee that is attempting to adjust to life on the outside, as well as overcome the discrimination he faces as an ex-convict.

Tattooed from arm to arm, Smith has the appearance of an individual that shouldn’t be messed with. Despite appearances, however, Smith is as polite and hospitable as a Southern grandmother.

Smith is a father of five, walks his children to school each morning and enjoys spending time with his family.

Smith served 27 months in the Deuel Vocational Institution of Tracy for burglary. Although he has been given his freedom back, he still feels isolated from society.

“As soon as you are sentenced to prison, you enter a recession automatically,” said Smith. “It doesn’t matter if the economy is doing good or bad, being a convict is a recession within itself.”

According to Smith, once inmates are released, they re-enter society with nothing. Most have no money, no job and many have no family.

He also mentioned that, as an ex-convict, it’s difficult to find a job. Smith says as soon as one reaches the question on the application that asks, “Have you been convicted of a felony in the past seven years?” all hope is lost.

“Society stereotypes convicts,” said Smith. “As soon as they find out you have been to prison, they turn the other cheek to you. Too many people have that once-a-convict, always-a-convict mentality.”

He believes that the only way somebody will give an ex-convict a chance is if they lie about their past. It is unfortunate, but nowadays, “you have to lie to better yourself.”

In the state of California, the standard procedure for the release of inmates includes providing them with $200, a shirt and pants (if their family can’t provide them clothes) and dropping them off at a bus stop in the county their crime was committed.

“If you can’t afford a bus ticket home, they buy you one and take that out of your $200,” said Smith. “Plus, you have to be in prison for longer than six months to even qualify for the money. If you only served three months, but still can’t afford to get home, you’re just out of luck.”

Smith refers to prison as a “revolving door” operation. He says that while in prison, you are guaranteed three hot meals a day, as well as a place to lay your head at night.

“There are no worries and you have no bills, since the State is paying for everything,” said Smith. “There are no responsibilities and so when inmates are released back into the real world, it is difficult for them to adapt.”

Although they are given another chance at life, Smith says freedom doesn’t come free. For many, it’s too much hard work, so they easily slip back into old habits and before they know it, they are back behind bars—the cycle continues.

California ranks among the highest in the nation for parolees returning to prison, according to Police Magazine.

“A lot of people see prison as their home,” said Smith. When they are released, they just think of it as them going somewhere for a minute, but they always go back home.”

Smith describes incarceration as just one step up from death.

“Being isolated from society for years at a time, sitting in a cage like an animal, showering with 20-30 other men and taking orders from guards younger than you, it’s hell. Nobody cares about you in prison, you’re nobody.”

Smith says that being an ex-convict has “lasting consequences.”

“It doesn’t matter how nice you are, what degrees you have, or how professional you appear to be. If you have done time, you permanently have a prison stamp on you.”

Smith mentioned that the prison system offers “pre-release education classes.” The classes are offered close to the release date of an inmate. The aim of the classes is to help inmates adapt to society and encourage them to establish goals for their future.

“The classes give you a chance to talk about what you want to do when you get out. It gives us the chance to really voice our opinions and we really need that. It lets you know that there is something better out there for you.”

Smith believes the program can be beneficial, but only for those who sincerely want to change.

The program leaders offer to do follow-up calls once inmates are released. The downfall to it, Smith says, is that nine out of ten inmates don’t have a reachable phone number, so the effects of the classes quickly fade away.

Smith suggests that there should be a vocational program offered prior to inmates’ release, assisting them in getting a job before they get out. He feels this can give inmates something to look forward to when they are released.

“We need a prisoner internship program. Upon our release, we should be placed at a temporary job. It doesn’t matter what the job is, whether it’s working at a dump or shoveling knee-deep in cow waste, we deserve a chance.”

The hardest part for Smith, after being released from prison, was re-adapting to society. He had to “adjust to not being behind bars.”

Smith feels no sense of compassion from the government. He thinks the state views inmates merely as statistics.

According to him, the system only cares about the money they are making off the inmates, not their well-being once released.

A report by the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation states that 47 percent of offenders released from prison in the fiscal year 2007-2008 returned to prison, for new crimes or parole violations.

“Just give me a chance to show that I am a good worker,” said Smith. “Let me show you that I really don’t want to go back to prison.”

Smith gets up early every morning, resume in hand, to look for work.

“No matter how good my resume looks, I am still a felon,” said Smith. “I am trying to stay focused, but I am starting to get frustrated.”

In addition to walking his children to school, he attends parent-teacher conferences frequently and he knows his children’s teachers and their friends.

He is a recipient of the General Assistance Program. “It has been very beneficial to me,” said Smith. “It gave me money and food stamps which allowed me to help out my mom, but it simply isn’t enough.”