Look Ma, More Debts!

March 2, 2022

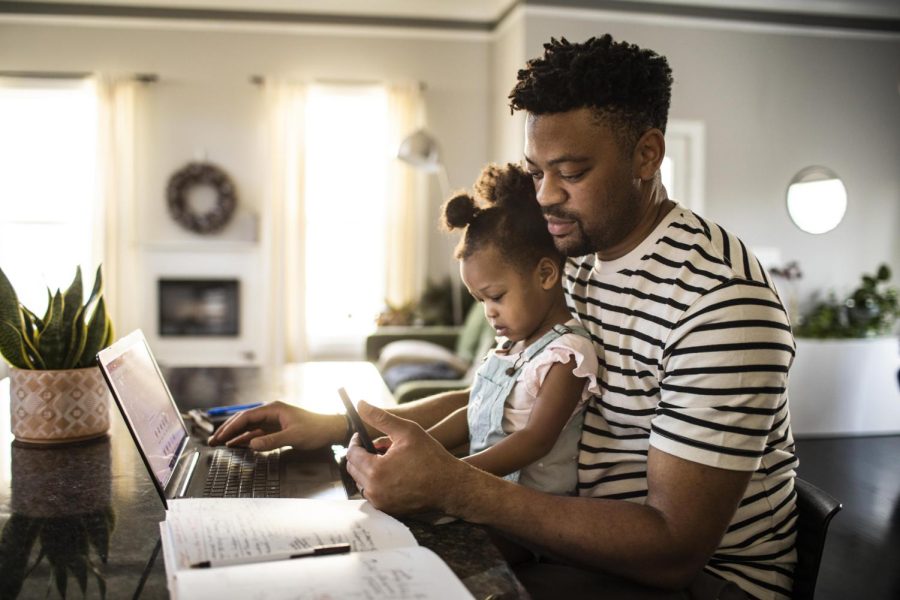

Paid family leave: A quirk of modern convenience or an overlooked need?

Can one put a price tag on a child?

Fortunately, there is no need to dust off the calculator or hire an accountant to determine the average budget of raising a child, as the USDA has published an estimated total of $233,610 in expenses required to raise a child into adulthood, without factoring in college expenses.

Mindful of the high fees associated with raising a child, time is yet another scarce resource that young families ought to manage, often at the peril of job stability and stable income.

Such a steep trade-off is endemic to the United States —the only industrialized Western country where no national paid family leave program exists. Unpaid, job-protected leave was instituted on Feb. 5, 1993, under the Family and Medical Leave Act (hereinafter featured as “FMLA”), though paid leave has yet to be nationally implemented.

Attempts to install a paid nation-spanning family leave program have gained fervor in recent years, with Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY), who authored the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act (“FAMILY”) in Congress on Feb. 4, 2021.

The Senate bill is bound to entitle all workers with partial compensation for sixty days since the start of paid family leave. Since its introduction, the FAMILY Act has been referred to a relevant Committee with no further legislative developments, indicative of low prioritization by Congress in addressing the matter of paid family leave.

By stark contrast, the duration of average paid family leave programs within OECD member states is 18.4 weeks.

While national lawmakers continue to demonstrate apprehension over introducing paid maternity leave, some cities and states have exercised the option of expanding upon the federal legislature to include a paid family leave. California was first in the nation to provide Paid Family Leave (“PFL”) as an auxiliary of the State Disability Insurance program, enacted by Senate Bill 1661 on July 1, 2004.

Under current jurisdiction, an employee is entitled to 60-70% of their highest quarterly earnings in wage replacement for eight weeks within twelve months.

PFL does not protect employees from termination of employment, albeit the California Family Rights Act (“CFRA”) mitigates the risk of sudden unemployment by requiring businesses with more than five employees to reinstate new parents with pregnancy disability for four weeks and/or child bonding leave for up to twelve months, with both concurrent with the duration of unpaid FMLA benefits.

In discussion of the how, of course, the principal question for some is rather why: “Why should we care about paid family leave?”

For public educators like Dr. Jennifer Eagan —a professor of Philosophy at California State University, East Bay and local Faculty Rights Chair at the California Faculty Association union — a full semester of paid maternity leave would allot sufficient time to welcome and nurse a child, recover from any outlying health concerns, and ensure that health complications or family-related emergencies don’t disrupt the academic schedule and the curriculum.

“On an academic schedule, you can’t always time when your kids happen. And as faculty, we don’t get an exceptional amount of leave or vacation time, [and] faculty need to work long enough to acquire sick leave.” At the moment, California State University Faculty receive thirty days of paid leave, but Eagan argues that a month is not enough to develop a bond with the newborn.

To prolong pregnancy leave, Eagan revealed that some faculty members opt to use their sick leave in place of family leave, though contending that “faculty may not have accumulated enough sick days” to cover the entire postpartum period.

The cardinal flaw behind the aforementioned practice is the conflation between disability and pregnancy. “Pregnancy isn’t a sickness,” and shouldn’t be viewed as such, claimed Eagan. Instead, “it is in the interest of the State of California to have things like healthy families,” with Eagan urging that the California State University system take action towards embracing more paid familial leave. Moreover, repurposing sick leave as family leave leaves the employee destitute of choice in the event of an actual health emergency.

Eagan suggests that the first step should be restoring childcare centers on-campus. “We used to have a child care center, but President [Mohammad] Qayoumi closed it in the mid-2000s, [citing the center] as an insurance liability,” recalls Eagan, expressing her bewilderment at the decision, as other CSU campuses, such as Stanislaus, Cal Poly SLO, San Marcos, Los Angeles, and Long Beach, all provide access to on-site child care centers.

Thus far, President Cathy Sandeen has not been receptive to the motion of reviving childcare centers, but Eagan believes that persuasion is a possibility: “I understand it could be costly, but it would increase productivity, be a tremendous perk for faculty and parents, and [save on otherwise] expensive childcare in the Bay Area.”

Aside from reinstating child care facilities and programs on-campus, Eagan and the CFA have sponsored AB 2464, which was first introduced by Assm. Cristina Garcia on Feb. 17 in Assembly. The proposed bill is forthright in its messaging, suggesting that the CSU system grant paid family leave for the duration of one academic semester. “The California State University system is in the business of providing a public service, and to treat faculty — who are public servants — with lower wages and insufficient paid family leave is inappropriate,” said Eagan.

As the financial costs of raising children escalate, parents will need to spend more time at work to compensate for a dwindling wage. Paid family leave enables employees to reclaim family time and return to work with a renewed sense of resolve: aspects necessary for survival in the increasingly inhospitable workplace environment.