An Exploration of Afrofuturism

A Look at the Past, Present, and Future of Afrofuturism with Nina Woodruff-Walker and Cal State East Bay Professor Dr. Nicholas L. Baham III

Afrofuturism is a cultural movement and aesthetic that explores the technology and genre of science fiction through a Black lens, shining a light on and critiquing the present-day dilemmas for people of color.

While the ideas behind Afrofuturism have been around as long as Black futurists have “envisioned a society free from the bondages of oppression,” the term “Afrofuturism” was coined by a white scholar named Mark Dery in 1993.

“Afrofuturism combines science fiction and fantasy to re-examine how the future is currently imagined and to envision alternative futures based on the Black diasporic experience and people of color (Wakanda Forever!). Afrofuturism seeks to reclaim and celebrate past and present African and Black Diaspora wisdom and progressive insights while augmenting how those insights can look and combine with technological and scientific innovation,” executive director at the Museum of Children’s Art in Oakland and double alumni from CSUEB Nina-Woodruff-Walker said, quoting CSUEB professor Dr. Lonny J Avi Brooks.

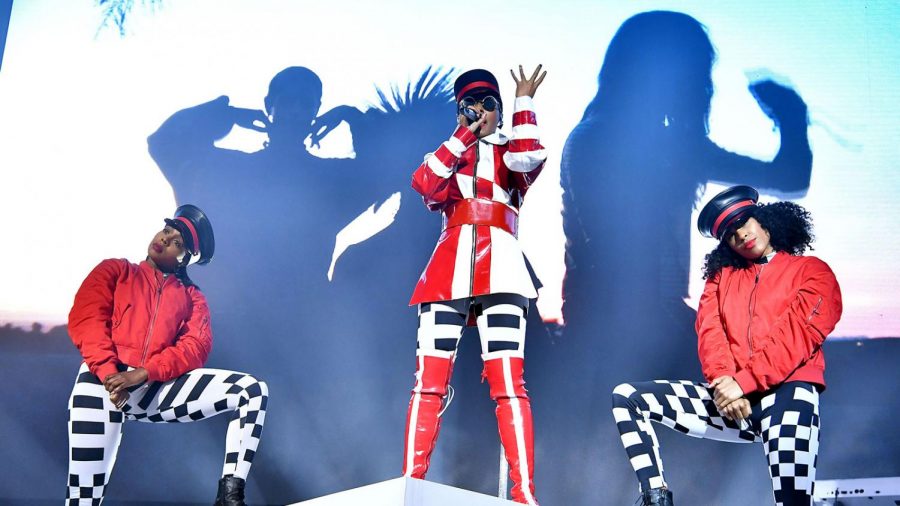

One aim of Afrofuturism and artists of the movement is to reconstruct Blackness in the art culture. Among the most prominent figures of the Afrofuturism movement are Octavia Butler, Sojourner Truth, Sun Ra, and Janelle Monáe.

Afrofuturism extends to pop culture in mass media through ways that, to a blind eye, seem to just be entertainment, including the film “Black Panther,” Janelle Monáe’s album titled “Dirty Computer,” and Octavia Butler’s science fiction novel “Kindred.”

Afrofuturism serves as a “cultural blueprint to guide society,” Clever wrote. The Afrofuturism movement acts as a guide that pushes society towards a future full of justice, equality, representation, and Black empowerment.

While Afrofuturism looks to the future, it is the history of Black people and Black culture that makes the movement what it is. This is a sentiment both Woodruff-Walker and Dr. Nicholas L. Baham III, a full professor in the Department of Ethnic Studies at CSUEB, emphasized.

Speaking on how Afrofuturism tends to critique the dominant power structures of the past, Baham said “Afrofuturism isn’t just forward-looking, it also looks backward too.”

“[It] can be accessed through centuries-old African folktales. It can also be experienced during the Harlem Renaissance or through the work of Octavia Butler from the 1970s… It is the past, present, and future. You cannot locate any of the aforementioned dimensions without considering history or culture. They are both requirements,” said Woodruff-Walker.

From prison abolitionists to dismantling the police state, there are many parallels to the past of Black people fighting against oppression to the present day.

Put simply, the ability to develop one’s own identity is a privilege that dominant power structures have always and continue to deny Black communities. This is especially detrimental to Black youth as they never envision an inclusive future with themselves represented so they don’t have the opportunity to develop a sense of self-identity.

“Typically in a white supremacist setting, people of European descent are posed as being in the present and future. That’s the way the old European exhibitions used to work. You’d walk into the exhibition hall and then they’d show you the primitives, who were from African nations, parts of Asia, Latin and Central America, and the Caribbean. Which means everybody outside of Europe is in the past. The idea is: what if we can as people of color insert ourselves into the future,” Baham explained.

Being a subgenre of science fiction, Afrofuturism is a direct response to the lack of representation and diversity in the historically white-dominated genre.

“It’s a decolonizing effort to free ourselves from being on the margins in the future,” Baham said.

Woodruff-Walker expanded on this idea of Afrofuturism being a decolonizing effort, “Afrofuturism offers a non-binary alternative to whiteness and white supremacy.”

The best part of Afrofuturism is that it is not just for Black people! Anyone from any racial background can explore the Afrofuturism subculture.

“Afrofuturism is not just for Black people, in the same way that anything that Black folks have created, whether that’s jazz, rock and roll, or blues, isn’t only for Black people. You want everybody to participate in this,” Baham said.

There are many ways to support the Afrofuturism movement such as supporting Afrofuturistic art and artists, watching a film, or reading a book about it. One way CSUEB students in particular can learn more about Afrofuturism is through the course our university offers on the topic.

The course is an upper division Ethnic Studies course created and sometimes taught by Dr. Baham himself. The name of the course is “Afrofuturism” and according to Dr. Baham, a very popular course, so look into it now if you are interested in enrolling. More information on the course can be found here.

“We’re trying to build an infrastructure for Afrofuturism at East Bay,” Baham explained when asked about the course.

While Afrofuturism is a beautiful aesthetic and movement with art that is unique and eye-catching in the ways it incorporates the Black perspective, it is also so much more than that.

“Afrofuturism is not just a movement, it is a theoretical perspective and discipline. You can support the movement by connecting with Museum of Children’s Art (MOCHA) who has a Community Futures School, oriented for BIPOC youth, co-designed by CSUEB’s Lonny J Avi Brooks. We have an upcoming event on Saturday, October 16, 2021,” promoted Woodruff-Walker.

For more information about MOCHA and the events that they host, visit their website.