Berkeley Film Festival spotlights local homelessness

November 14, 2016

It’s 9 p.m. on Saturday and nobody stirs at the East Bay Media Center. Around 20 film-lovers huddle in the small, brick-lined room that smells like patchouli oil and old wood, while Amir Soltani and Chihiro Wimbush’s powerful documentary “Dogtown Redemption” plays on the screen.

Mel Vapour, director of the Berkeley Video and Film Festival and vice president and chief financial officer of East Bay Media Center, said the 25th Annual Berkeley Video & Film Festival received over 90 submissions this year but only 50 films made the cut.

The festival took place over two weekends this year, from Oct. 28 to 30 and Nov. 4 to 6, longer than previous years. According to Vapour, it will potentially expand to weekday showings next year with a focus on thematic films.

“Dogtown Redemption” focuses on the Alliance Metals recycling center in West Oakland and the impoverished people who labored there before it was shut down by the city on Aug. 20. The business once provided work to dozens of the city’s unemployed, homeless residents, who collected hundreds of cans, glass bottles and plastic containers from dumpsters and residential garbage cans around the city every night, earning some up to $100 per day after they recycled them.

Over the course of the 90 minute film, the stories of three recyclers emerge: Jason Witt, a connoisseur of garbage who has mastered the art of balancing hundreds of pounds of recyclables on his bicycle; the quirky Miss Hayok Kay, a former drummer in an 1980s polka band; and Landon Goodwin, a former minister who eventually left the streets and his addiction behind to reunite with the church.

Their stories are impactful because homelessness is a condition that hits close to home for Bay Area residents. The East Oakland Community Project, an organization that offers emergency and transitional housing in Alameda County, reports that 49.2 percent of the county’s 6,215 homeless population live in Oakland. Like Witt, approximately 560 homeless people living within Alameda County have HIV/AIDS.

At the end of the night, the film won the Grand Festival Award for Best Documentary. In a question-and-answer session after the showing, filmmaker Soltani told the audience that the idea for the documentary came to him when he moved to West Oakland 10 years ago into his brother-in-law’s condo and heard people rummaging through the garbage cans in the early hours of the morning.

He borrowed $10,000 to buy a camera and he thought it would be enough. “I don’t think of myself as a filmmaker,” said Soltani. “We were climbing the Everest but I thought it was a hill.”

Almost $600,000, 250 hours of footage and seven years later, the movie was completed in Sept. 2015. “The greatest gift to have when you’re making a film is time,” said Soltani.

Throughout the filming process, the crew and recyclers established a relationship that Soltani credits to safe years of filming at all hours in the Oakland streets without incident. This level of comfort also allowed the filmmakers to capture the recyclers’ most intimate moments: from Witt shooting up heroine to Miss Kay sobbing on the grave of her boyfriend, who passed away from illness.

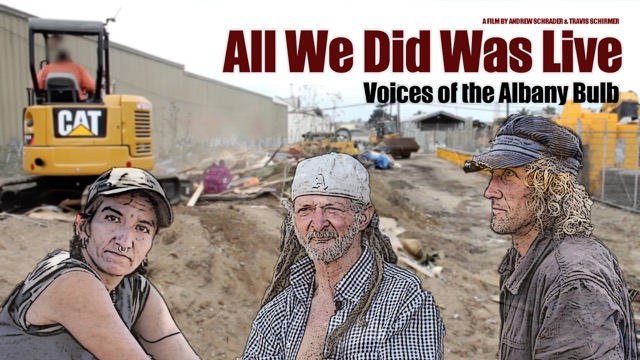

Soltani said because of the characters’ unpredictable lifestyles, it was impossible to adhere to a strict filming schedule, a challenge that filmmakers Andrew Schrader and Travis Schirmer identified with during the making of their documentary, “All we want to do is live,” which played at the festival before “Dogtown Redemption.”

The documentary highlighted the same familiar scenario: gentrification in Berkeley and Albany through the eyes of two displaced homeless people, Amber and Thomas, who lived at the Albany Bulb, a landfill-turned-park, before the city cleaned up the area in 2014.

Like Amber and Thomas, dozens of homeless people made camp at the Bulb bordering the San Francisco Bay, until the city scattered them to neighboring cities like Berkeley and Oakland in an effort to turn the area into a park.

The documentary was inspired by a newspaper clipping about the encampment that focused on the relocation of the Albany Bulb residents to a Berkeley industrial park.

“We had no idea what we were doing and we went to a camp in that dirt lot and we didn’t know anybody there,” said Schirmer. “We just literally walked up and people didn’t trust us. It took awhile for us to stand around and talk to people and then people agreed to talk to us. I think you just can’t have the camera right to begin with.”

The city threatened to dismantle the encampments at the park and Shrader planned to film during the week of packing that would ensue after the eviction notice was served, however that didn’t happen. The camp was bulldozed without formal announcement and Shrader thought the movie was over before it started.

“When the camp was bulldozed, I thought that the movie wasn’t gonna happen,” he said. By a stroke of luck, Schrader arrived with cameras at the site shortly after the bulldozing started. Schrader said most of the footage in the documentary was shot as tests for the film’s proof of concept, information gathered in the beginning stages of a project that is used to determine how achievable it will be. Schrader admitted he didn’t have a full vision for the film until Schirmer, their producer and Ilana Sawyer, curator of the Humans In Between Homes project, took the reigns.

The film was shot twice a week over about seven weeks and cost $1,500, according to Shrader. The film won the Best Locally Produced Short Documentary at the Berkeley Film Festival. Schrader said the next step will be to make the film available online through a channel that’s geared toward social justice issues.

Around 14 people judged what films met the criteria, which ranged from tech finesse to film quality. The festival screens everything from independent films to local documentaries, short experientials and foreign films. Vapour said the festival recently received more interest from other countries, such as Russia, Australia, Sweden and Hong Kong and is slightly changing direction to accommodate foreign content.

“Berkeley has a certain cache and I think they like the audiences,” said Vapour. “There’s a real specific pointed interest in cinema.”

Vapour said there is rekindled interest and overall wider acceptance of independent films. “It’s an upward battle,” he said.