South County Homeless Project helps homeless get off drugs, get psychological help, and get back on their feetwith

Statistically, it is true that Alameda County homelessness has decreased by some 10 percent in the past three years, yet the problem persists.

Statistically, it is true that Alameda County homelessness has decreased by some 10 percent in the past three years, yet the problem persists.

“On any given night, there are 1,300 people without a bed in Alameda County,” said Calvin J. Walker, Director of the South County Homeless Project.

This particular shelter houses single adult males and females, who were each referred by a case worker after being diagnosed with a mental illness from local psychiatric hospitals.

No walk-ins are accepted, yet even with this restriction in place, their space is limited and their work is vital.

“They saved my life, and I want you to put that in there,” said ‘Mr. B,’ a resident at this facility.

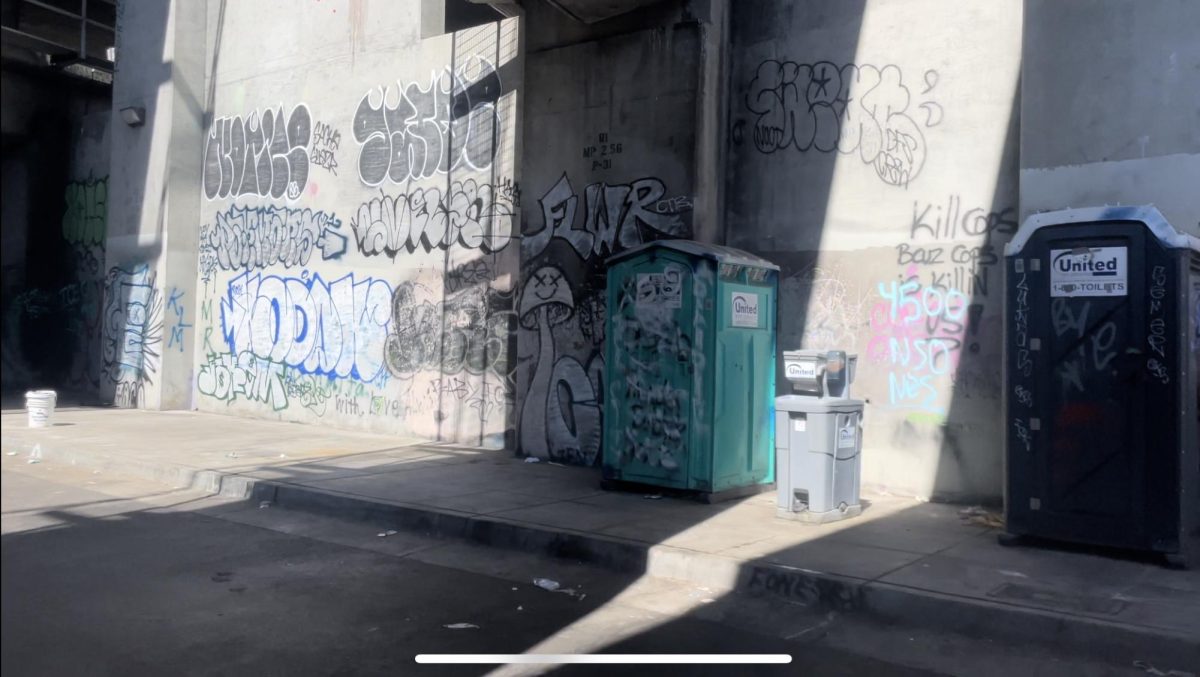

Set back a bit from the busy intersection inside a chain-link fence, it looked like a derelict ex-business gone to seed from the outside.

The casual passersby at Santa Clara and A Streets would never suspect that people were housed in the nondescript, rectangular pinkish and grey building.

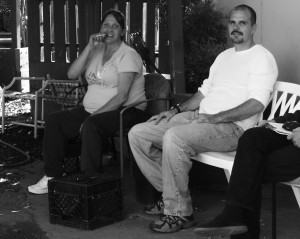

A handful of residents were outside enjoying the sunshine, and two or three people sat in the shade of “the outdoor smoking lounge” several yards from the door in a spot well away from foot traffic, except for a large, mottled looking cat that was nonchalantly noshing from a nearby dish.

Inside, however, there was a large, very comfortable looking common room with several people engaged in conversational pairs or trios. A few people were reading and the television received little attention.

At either end of the common area stood a door each for the male and female dorms, each of which held 12 beds. Every bed would be occupied that night.

“That’s our old name,” said Walker, gesturing toward the backward lettering on the outside of the glass door.

“We haven’t had that name for about eight years, so our newest rendition of the same organization is ‘Building Opportunities for Self Sufficiency,’ (BOSS) and this place has been around since around ’89,” he explained.

According to their website, BOSS was first established in 1971 as a direct response to the closure of mental health hospitals, which put many mentally ill men and women onto the streets.

Today, BOSS serves over 1,500 homeless families and individuals with multiple barriers to self-sufficiency. This is one branch of the Berkeley-based organization.

“This is a mental health facility, so years ago when we were support services, we would be able to take people right off the street, and then we would screen them for mental illnesses and bring ‘em in,” Walker said. “Now, we have a contract with behavioral health care, which is Alameda County Mental Health Services, and so we have to take referrals from the system, so that’s restrictive.”

“We get referrals from John George, Woodrow Place—all the other hospitals, and, for the most part, case managers of the system,” he added.

When caseworkers eventually catch up to their clients—possibly in jail or a hospital somewhere—they will call this BOSS facility to refer a client for residency and treatment.

“We’re like the entry point back into the mental health system,” Walker said, “and our jobs are to help stabilize people by overseeing them taking their medications on a regular basis, and it takes them (the patients/clients) two or three weeks to go from unstable to stable—if they’re taking their medication and not doing anything else.”

The length of a resident’s stay here depends largely on the honest effort and steady improvement of each resident.

“While they’re trying to adjust to the environment, we try to create an environment that is home-like and community-oriented, so strangers get to meet each other and try to get a level of trust with each other so they won’t steal off one another, and so they’ll help each other out feetwith little things,” Walker said.

They rely on the greater abilities and more advanced degrees of healing in some to augment and offer moral support to those who are still struggling to adapt.

“Some of them need assistance, so we try to create an environment where everybody helps one another, and then we do groups that help people to bring back the skills that they already have,” he added, “and so that’s what our job is here”.

With this in mind, it appears the staff members were all very adept at their jobs. The residents were aware that their individual determination on the road to recovery was a seminal factor in the length of their stay.

The average stay in the program is four to five months, but some choose to leave the system rather than do the hard work necessary to become, as Walker put it, “un-addicted.”

With permanent housing, possible employment, and re-entry into mainstream society being the ultimate goals, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) was also mentioned as a benefactor.

Walker emphasized enthusiastically how the staff would be with the residents for the long haul, as long as they were making an honest effort. Progress follows effort.

If ne’er do wells were in attendance, they did not make their presences obvious.

Everyone in sight was convivial, neat and well-manicured, mostly smiling, with nary a sullen face in the lot.

Some were almost giddy with gratitude for their good fortune in gaining admittance to the community within those walls.

“Mr. B,” a young man of 32, attempted suicide, landed at John George Hospital, and considered himself very fortunate to be where he was. Diagnosed clinically depressed, he has been taking his meds, is in a comfortable situation and working hard to get better.

“[My health] is better than it was, but it still has a long way to go,” said ‘Mr. B.’ “I don’t know if I want to go back to the workforce. For now I just want to get my mental health in order.”

Another resident, who called herself “Sunshine,” was an alcoholic who lived with her mother for three years following a failed marriage.

She became homeless when her mother moved in with her sister following a house fire.

Sunshine and her sister did not get along well together.

“So I moved to Pittsburg and into a program called ‘Love a Child Mission,’ and I stayed there a year and had Bible study twice a day,” Sunshine said. “I got really close with God, and that’s why I stayed, ‘cause it’s not a very good program at all as far as getting a person back on their feet.”

After being kicked out of that program, she bit the bullet and moved back to Hayward where she stayed with her sister for two weeks.

“And then I came here,” she said, “and I’m getting myself back on track. I’m getting my act together, doing what I need to do. This is a really good opportunity for me.”

“We all eat together—you get your social skills back. This helps me get out of myself. I do take meds. I’ve been diagnosed bipolar,” she said.

Sunshine’s goal is to be well and out on her own.

Another resident, “Randy”, also expressed a determination to make every effort to get well.

He was diagnosed as schizophrenic, and has only been in the program for three weeks.

One source, citing 2007 statistics, claimed 2,000 of Alameda County’s 6,000 homeless people have mental illness, drug- and/or alcohol-related problems. Another source claimed 6,215 – 10,425 homeless for the same time period.

Regardless of the numbers, statistics cannot provide a bed, a meal or a safe place to heal a mind.

Statistics are everywhere, and they vary depending on the source. Even good “hard” stats from government agencies, or in depth research projects are nebulous, at best.

How would one go about counting an entire population that, for the most part, chronically lives off the grid?