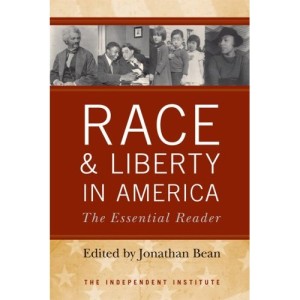

Race & Liberty In America: The Essential Reader” has the endorsement of many prominent intellectuals. With four pages of good reviews at the beginning of the text, the reader can feel confident that he or she is reading work that is approved of by all political spectrums: the conservative Shelby Steele, the libertarian Andrew Napoltano and the progressive Juan Williams.

Race & Liberty In America: The Essential Reader” has the endorsement of many prominent intellectuals. With four pages of good reviews at the beginning of the text, the reader can feel confident that he or she is reading work that is approved of by all political spectrums: the conservative Shelby Steele, the libertarian Andrew Napoltano and the progressive Juan Williams.

Juan Williams’ endorsement is generous, as the prolific author and pundit writes, “If you are interested in the real history of the civil rights movement in America-the radical ideas that set it in motion no matter where they came from-get ready for an intellectual thrill ride,” said Williams.

Williams’ proclamation of “no matter where they come from” is key here. The Independent Institute is a classical liberal (more commonly characterized as libertarian) think tank based out of Oakland, California. According to such an ideology, markets are supreme and freedom of individual is even higher in rank.

While the ubiquitous additions to a history of America’s racial evolution is here – Martin Luther King, Jr., Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglas are present – the out of the box is there.

By “out of the box” I mean the likes of Robert Taft, the senator known as “Mr. Republican.” Taft appears several times – in a sizing up by prospective voter Zora Neale Hurston and in the transcription of his effort to censure Mississippi Dixiecrat senator Theodore Bilbo, an extreme racist whose rhetoric was beyond the pail even in the late 1940s.

This book, however, tries to please everyone and winds up at points offending everyone. Unlike many right of center accounts of racism, it doesn’t avoid the Southern Strategy and Republican efforts to pick up conservative votes. It does lay most of the blame for pre-Civil Rights policies of segregation at the feet of conservatives.

In more recent history, on the other hand, this volume lays the blame for racial division at the feet of progressives. This sudden lurch is hard to find credible.

With such strong attacks on affirmative action and the Civil Rights Act by figures such as Barry Goldwater and Milton Freidman, it seems suggested by the text that minorities, who had been oppressed for centuries, weren’t in need of a head start into equality. While it is ideologically sound and noble to say that all individuals should be treated equal, oppression does leave an indelible historical stain.

A personal connection was made with the inclusion of the Roberts Court’s decision on Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District. The opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts provides an ideal bookend, with the sensible proclamation “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Having grown up in Seattle during the time of Seattle’s educational race-based quota system, I’m all too familiar with the cosmetic nature of that policy – in which a handful of minority and disabled students were able to go to the few good schools in the district while little effort was put in to actually improving the schools near where they live.

It’s not just the political speeches and rulings that stand out in Race & Liberty but also the excerpts of writers such as H.L. Mencken and George Schuyler. Schuyler eloquently makes the case against Roosevelt’s wartime internment of the Japanese in “Their Fight Is Our Fight,” particularly connecting the oppression of those unfortunate enough to share ancestry with the United States’ WWII enemy with segregation of the south, persecution of Jews in Germany and imprisonment of dissidents in the Soviet Union.

While not authoritative, Race & Liberty In America is every bit the intellectual thrill ride Juan Williams asserts At the very least, it complicates the simple narrative of civil rights history that most of us have. At the most, it inspires and makes us think.