The Importance of Generational Storytelling

February 1, 2023

The other day while I was in Half Priced Books, a memoir caught my attention. Upon taking a brief look, I found out that the author — a Bosnian refugee — grew up with my family in the small northern town of Brčko prior to the Bosnian war in the 1990s. After buying the book, I brought it over to my grandmother’s house to ask her about her experience as a mother of two during the most deadly conflict on the continent since the Second World War.

Her experience, much like that of many Bosnian refugees, is one of personal uniqueness, yet collective familiarity. Stories of neighbors turning on each other, the West neglecting to help, and that of childhood friends who never returned from the front lines are all common memories of those refugees who were driven 6000 miles away from their homes and their country.

As my grandmother spoke of her life during the war, the TV covered the latest news of Western aid to Ukraine. “When we were getting shot in the streets and our houses [were] getting bombed, we didn’t receive anything,” she explained. While many survivors of the war that I have spoken to feel immense sympathy for those in Ukraine, the older generations cannot stress the anger they felt in the Western response to Bosnia 30 years ago.

My grandmother recalled instances of halfhearted aid from the West, often in the form of expired canned food dated back to the Vietnam War. Worse yet, humanitarian planes above delivered cans of pork to the Bosnian Muslims being massacred below.

As I watch the coverage of the conflict in Ukraine, it is hard to miss the striking similarities between the present battle for Kyiv and the war in Bosnia during the 90s’. However, an unmistakable difference is the neglect many Bosnian Muslims (also referred to as ‘Bosniak’) communities faced from Western countries. It wasn’t until after enduring years of massacre, genocide, and abuse that Bosniak families received even a fraction of support that we see today for Ukraine.

As my grandmother put bluntly, yet truthfully, “The world doesn’t bat an eye at Muslims in need, whether it is Bosnians, Arabs, or any other ethnicity.”

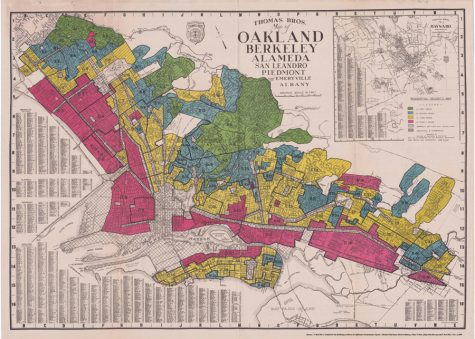

I asked my grandmother to share her story of immense hardship following forceful relocation from her family home in Brčko — long gone from incessant shelling — to her current apartment on the outskirts of Hayward.

After the dissolution of what was once Yugoslavia, Bosnia became the site of an international quagmire between the nascent Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatian and Serbian insurgents, with Brčko as the epicenter due to the town’s ethnic diversity and its central location on the crossroads between Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia. The fighting began with friends turning on one another; coworkers and neighbors of over 20 years suddenly pointed guns at each other after radio-fed propaganda from Belgrade began scapegoating certain groups for perpetuating war. The atrocities began as Bosniaks were being massacred by Serb police forces in the street, with my family knowing many who lost their lives to senseless violence. While we had originally lived in the center of the city, my family quickly fled to the edge of town — the final bastion of safety for any Muslim family in the area — with as few belongings as there was time.

For the next two weeks, my family would stay at a relative’s house in Vražići, a small farming municipality on the outskirts of town. Soon after finding what they thought was safety, bombing runs moved from the city to the farming communities. In a last ditch attempt to leave their town, my grandmother took my mother and aunt away — both in their teenage years at the time — while my grandfather stayed behind as a military conscript for a few months.

Leaving Vražići, the trio hired a man to take them to Srebrenik by truck: the closest Muslim-majority town that the war’s brutality had yet to reach. The truck driver, however, couldn’t use the main roads due to the conflict, forcing them to travel through mountains and hills. The man’s truck, a small, two-door with less than 100 horsepower, was unable to haul the two families up the steep terrain without the truck stalling. As a result, both families had to walk through the dense forests as the truck hauled their belongings to the town. Once they reached Srebrenik, muddied and tired, my family boarded one of the last buses that took them out of the country to Kranj, a Slovenian city.

The attitudes towards the refugees passing through Slovenia were unfriendly at best. While every ex-Yugoslav looks more or less similar in appearance, my grandmother and mother remember the frequent and relentless discrimination they faced during this time, as the Slovenians would detect Bosnian accents and language, making those fleeing the conflict targets for dirty looks and name calling.

In Kranj, my grandmother was able to secure a bedroom at a friend’s house — a fellow Bosniak woman who housed refugees on their way to the north. Learning of a Bosnian refugee camp in Maribor, a city a few hours away from Kranj, incentivized my grandmother to leave, allowing her to reunite with my grandfather who had just left the frontlines.

As recalled by both my mother and grandmother, the refugee camp in Maribor was a huge mess with crowds and families lined up to have their names down on a list to be placed in a queue for housing. Starting anew in Slovenia seemed less than promising in lieu of being treated as second class citizens and relegated to menial cleaning jobs. Rather than staying in Maribor, my family followed other friends to Mannheim, Germany.

Mannheim, as described by my whole family, was the best time of their lives. It was a town where virtually every refugee from their original town had made a home; where new bars and restaurants run by Bosnians popped up every week; where family and friends could party in the streets, all the while forgetting that their homes were being bombed and looted a few borders south, never to be returned to. My family uprooted themselves during their stay in Germany, with my mother marrying my father in the span of a few years since first arrival.

My grandmother and the rest of my family would’ve stayed in Mannheim for the rest of their lives if not for their refugee visas expiring, ending their blissful German livelihood. By abandoning their homes again, my family had left the simple yet joyous memories that made them forget the reality that ravaged Bosnia.

With the war coming to a close, my family was left with two choices: to return to their Brčko house that had been reduced to unrecognizable rubble within a community, wounded by ethnic division and bloodshed, or to settle in the United States. My aunt was the first in my family to move to Hayward, serving as the catalyst for the rest of my family to restart their lives in the US. It wasn’t until a decade later that my grandparents made the trek back to Brčko, seeing the faces of those who once pointed guns at them walking down the street, greeting and smiling at them as if the war never happened.

Documenting the stories of individuals like my grandmother is important not only for its historical context, but also as a testament of community resilience by those whose cultures and beliefs were considered lowly and unworthy of protection — not only by oppressors, but by those who were given the title of international mediators and peacekeepers.

Generational storytelling is essential for the sheer fact that I wouldn’t have known about my grandmother’s story if it weren’t for a random memoir I found at a Half Priced Books. The story of my grandmother is one of millions — refugees being displaced, killed, or forgotten on a daily basis, having to forsake their homes to settle in safe havens for immigrants. Ours turned out to be the Bay Area. If it weren’t for the unfathomable journey and strength of my family, this story would’ve been lost and forgotten. Condensing my grandmother’s story into a single article doesn’t do it the justice it deserves, although writing this story for her is a privilege in itself as I continue to learn about how brave she truly is.