Bay Area: Progressive Politics on a Racist Foundation

October 5, 2022

While slavery has been officially abolished with the passage of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, the legacy of the peculiar institution has persisted into modernity by issues of economic disparity and implicit segregation in urban areas.

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Union General William Sherman and Secretary of War Edward Stanton gathered with a large group of black leaders in 1865 to discuss the best course of action to make adequate reparations to the formerly enslaved. Garrison Fraizer was one of the black men in that meeting and was even elected by the group to speak in a New York City Tribune article

titled “Negros of Savannah.”Fraizer said, “the way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land.” In lieu of his declaration, thousands of acres were set aside through a plan called “Special Field Order No. 15,” initiating the process of granting reparations by Abraham Lincoln days before his second inauguration on March 4, 1865. This plan, which would give no more than 40 acres of tillable land to each family of former slaves, never succeeded.

Conditions didn’t improve as blacks had to move into highly dense populations with low incomes. In an autobiography written by Booker T. Washington, “Up From Slavery,” he recalls leaving Hampton University during the breaks and going home to Malden, West Virginia, to see his mother’s neighborhood. Malden was a mining outpost, dense and with poor living conditions for most black people who lived there. By today’s standards, the living situations have not changed much, and the same conditions persist for people of color.

Once a fortune has been established, it is much easier to create more wealth. Hence, the wealth that white Americans continued to grow over 200 years allowed them to grow their wealth faster, putting blacks out of reach in many areas.

Today, higher populations of minority groups continue living in lower-income areas where market values are appraised at less than similar single-family houses in predominantly white neighborhoods. The persistent pattern of discriminatory disinvestment within low-income neighborhoods often renders them food deserts due to the absence of access to healthy, affordable, and fresh food options. In lieu of local food crises, the subsequent overconsumption of fast food, and their close proximity to industrial areas with poor air quality, minorities residing in inner-city neighborhoods are highly susceptible to health conditions, such as asthma and diabetes.

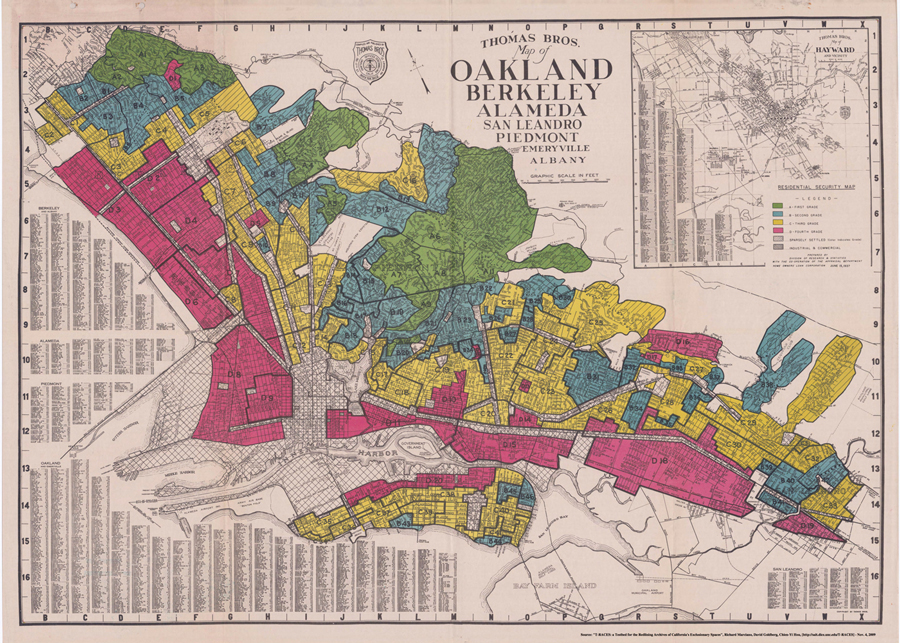

However, these developments are not accidental, but rather are a result of “redlining:” the practice of deliberate neighborhood segregation, stemming from the negative perception of minority communities. The lingering effects of segregation become evident by looking at the redlining maps of neighborhoods in any major city.

Oakland is one such city. A large push to move to the suburbs of the Bay Area was in vogue in the 1930s, with white families being the first to move to the hilly outskirts of Piedmont. Advertisements for these new developments were steeped in racist rhetoric to appeal to white buyers and deter minorities. Callous and offensive, such branding was completely legal under segregation.

As white families moved into single-family homes away from the center, industrial areas were the only parts of the city that had been left to minorities, lowering the housing market values in sections with a high minority population. Financial providers perpetuate this cycle by denying people of color housing loans from banks and creditors to relocate to predominantly white, affluent areas.

Racial discrimination in real estate was made illegal in 1964 under the Civil Rights Act, though the damage has already been dealt with since white communities had become entrenched in their neighborhoods through inheritance or favorable real estate conditions. For instance, the Bay Area is 52% white, however, Piedmont is 70% white.

Centuries of slavery and racial segregation have left minority populations in an unbeatable race to catch up to the white population, most evident in the median income levels for whites vs. blacks, in the job discriminatory market, as well as the percentage of home ownership in the country.

While the Bay Area is progressive, issues persist. To ensure that minority communities are afforded the privileges of white Americans, creating fair opportunity is not an equitable solution. However, smashing barriers, removing obstacles, and empowering people of color are.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the contributing authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Pioneer Newspaper or its editorial staff.