Among American institutions, the military has a long, storied tradition equaling that of the church, Congress, the Supreme Court and the White House. The armed services (Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps) have a unique culture and code of rules and behavior that is instilled in each of its members yet has proven remarkably steadfast in its principles, rivaling only the church in that respect.

Among American institutions, the military has a long, storied tradition equaling that of the church, Congress, the Supreme Court and the White House. The armed services (Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps) have a unique culture and code of rules and behavior that is instilled in each of its members yet has proven remarkably steadfast in its principles, rivaling only the church in that respect.

The recent injunction by U.S. District Judge Virginia Phillips in Riverside ruled that the military’s “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy was unconstitutional, violating the constitutionally protected rights of due process and free speech. Phillips, in her ruling, ordered the military to stop enforcing the controversial policy, which since its 1993 implementation has seen over 13,000 service personnel discharged based on their sexual orientation.

President Barack Obama, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the Pentagon’s top leaders have all publicly stated their opposition to the DADT policy—however, as Judge Phillips has demonstrated, the courts are currently the driving force towards enacting any change. Congress likely lacks the votes necessary for a repeal, and were it to attain them, has already declared that it would leave the decision to the Pentagon.

Many of the discharged gay, lesbian or bisexual personnel were serving in highly skilled and sensitive MOSs (Military Occupational Specialties). Lt. Dan Choi, a West Point graduate and U.S. Army Arabic linguist, announced he was gay on MSNBC in 2009 and was promptly discharged by the Army for violating the DADT policy. After Phillips’ recent ruling and the military’s acceptance of openly gay and lesbian recruits the subsequent week, Choi re-enlisted at the Times Square recruiting station in New York—his request is awaiting processing.

Choi is one of 59 Arabic and nine Farsi linguists who have found themselves discharged from an invaluable MOS within the service—with the U.S. military embroiled in wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the need for reliable translators and interpreters cannot possibly be overstated. Discharging service members who fulfill such crucial roles in our military operations is not only discriminatory and unjust, it is poor military judgment—the lack of qualified linguists places our troops in greater danger than any assumed reactions to allowing homosexuals to openly serve.

And while many who oppose the repeal of DADT point to the fact that the military’s closed, insular culture is unlikely to handle any change of the policy in a tolerant fashion, surveys of current active duty and reserve personnel indicate that only about 36 percent of men in the U.S. Army oppose gays openly serving—down from 67 percent in 1992, when the policy was implemented, according to the journal International Security.

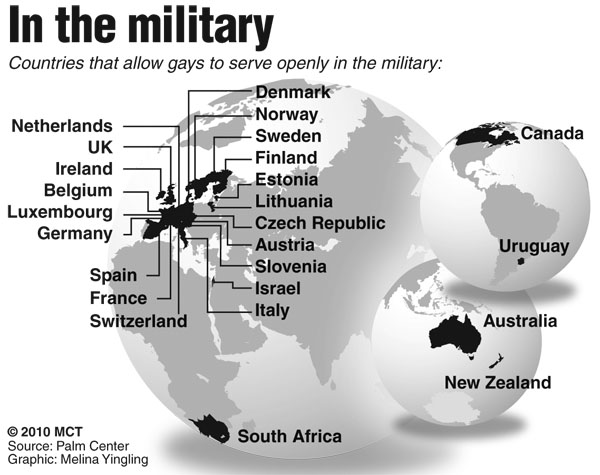

Our allies in NATO have taken a far different approach to the issue of gays in the military—indeed, the only nations in the alliance that don’t allow homosexuals to serve openly are Turkey and the U.S. The UK, who ended the gay ban in 2000, reported in 1995 that two-thirds of military personnel would be unwilling to serve alongside gays. Upon its repeal, three people resigned. Similar circumstances were reported in Canada, Australia, Germany and Israel, according to the Palm Center research institute of UC Santa Barbara.

Gauging how the U.S. military feels about the policy is difficult, since going on the record about DADT could possibly endanger the careers of personnel currently serving through unintentionally outing a brother- or sister-in-arms. This further serves to highlight an inherent problem with the DADT policy—the knowledge of one’s own or another’s sexual orientation could lead to possible self-incrimination or a “poison-pen” letter where a person could be outed anonymously by a vindictive colleague.

In the interest of military readiness, neither the discharge of qualified, skilled and trained (at the taxpayers’ expense, to be sure) gay personnel nor the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship that the military under DADT imposes on them makes a lot of sense.

The overriding sentiment among members of the military, both past and present, is the dependence on one’s brothers and sisters—the other guy or girl “in the foxhole,” to employ some outdated military parlance. No matter the situation off the battlefield, when the bullets and bombs fly, one is expected to have his or her comrade’s back, and vice versa. In war, your life is literally in your buddies’ hands.

For those who have served or are currently serving, this is an unalienable truth, almost painstakingly obvious in its telling. And for those on the outside, ready to dictate the rules for a military we support (though not necessarily the policies), it is important to bear that truth in mind as we attempt to rewrite the rules of conduct for that most venerated of American institutions.

When President Truman decided to integrate African-Americans into the military during the Korean War, he listened to much of the very same arguments we hear today about gays from the military’s leadership—and ignored it. “Why can’t President Obama do the same?” writer John Grant asks. “There comes a time when decisions need to be audacious.”

Allowing gays to openly serve may be considered audacious. What is truly audacious is that gay and lesbian service members who are willing to put their lives on the line in service of our nation—a nation that tolerates most everything, except allowing those same homosexuals to live their lives openly in the service—are being drummed out and made a political issue to be tossed back and forth each election cycle.

We don’t need any more consideration about repealing DADT—we owe it to the proud LGBT servicemen and –women who have and are still willing to defend our nation, no matter the personal cost or hardship.

Given all this, we at The Pioneer recommend that everyone support Judge Virginia Phillips’ audacious decision, and that DADT be immediately relegated to the proverbial “dustbin of history.”