Debt as a Game of Tug-O-War

Political squabbling by both parties masquerading as an economic plight. How do we reconcile?

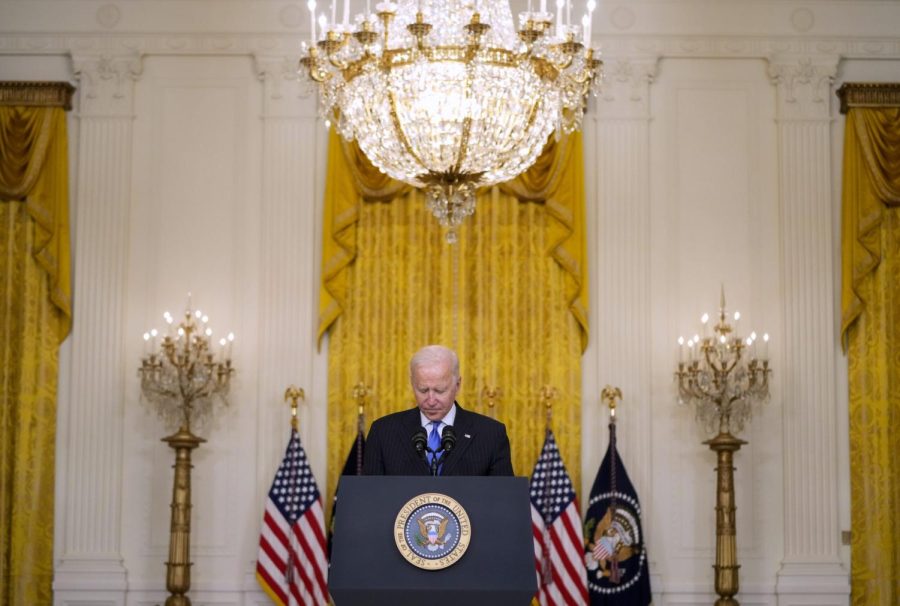

President Biden signed a bill on Oct. 14, authorizing a temporary debt ceiling raise to $28.9 trillion. Such an emergency injection of $480 billion is expected to last until Dec. 3 to ensure uninterrupted operation and fulfillment of government obligations, albeit Congress will need to provide a long-term solution until the date elapses.

Political maneuvering and bitter party quarreling are largely to blame for the debt limit crisis, evident by Senate and House voting results. Senate Democrats and eleven Republicans voted in favor of raising the debt ceiling, with 38 Republican Senate members opposed to the motion.

House presents a much starker image of irreconcilable partisanship. The Senate bill to raise the debt ceiling was ultimately passed, based on 216 unanimous Democrat votes. In contrast, all 206 representatives poised against the motion were Republican— a nearly unanimous vote, bar the six Republican and one Democrat representative who abstained from voting. The debt ceiling has become an instrument of political leverage.

Such manifest political meddling, compounded by market contractions and upsets due to the COVID-19 pandemic, instigates unnecessary public trepidation towards current economic conditions. “The debt limit is a crisis that happens regularly because it is self-imposed,” said Dr. Filippo Rebessi, an assistant professor of Economics at California State University, East Bay, specializing in Public Finance and Macroeconomics. “[Raising the debt limit] has nothing to do with fiscal sustainability of the United States,” affirmed Rebessi, continuing to state that “when parties are in power, they want to spend; when parties are not in power, they want fiscal responsibility.”

It is worth noting that both Republican and Democrat administrations have previously been credited with expansions of U.S. debt.

The threat of a debt default might be substantiated in the event of anemic economic growth. To assess the current economic vitality of the U.S., Rebessi prompted the question: “Do we believe that the U.S. economy will keep growing in the next 10, 15, 20 years at a similar rate?” In response to the constructed question, Rebessi anticipated that the U.S. is capable of sustaining economic growth by an annual estimate of 3-4%. However, the return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity and growth levels may be more sluggish than some of us would like to hope.

If the U.S. is able to maintain economic growth through productive policy initiatives over the medium-to-long term, debt interest will remain low. According to Rebessi, the current economic upset over debt limits is merely a symptom and a result of a slow recovery.

Rather than economic factors, it is political polarization that is harming robust growth. In expressing his professional opinion, Rebessi believes that the arbitrary debt limit is superfluous and should be eliminated, citing that the “debt limit is increasing economic uncertainty.”

Furthermore, Rebessi argues that “having a fixed debt ceiling is not a sensible target for policy,” as debt levels directly correlate with GDP metrics. Provided that the chief aim is to tether debt as a percentage of national GDP as a policy target, “debt would keep growing at the same rate as GDP, eventually hitting the debt ceiling,” outlined the professor.

While Rebessi contends that the debt ceiling could prove useful as a “way to get both parties to sit at the table,” these compromise-inducing powers have not been sufficiently exercised to warrant the preservation of the debt limit mechanism. “We already have enough problems; we don’t need artificial ceilings,” concluded Rebessi.

However, Rebessi does not have faith in the obsolescence of the debt ceiling any time soon, claiming that “there is no interest in eliminating the debt limit, not in this climate.”

Drawing upon historical precedent, Congressional gridlock over debt ceiling increases last occurred in Oct. 2013, which spurred over policy concessions and partisan interests. Whether this time will be any different remains to be seen.