‘Ghost Town to Havana’ film inspires, connects

March 15, 2017

For many people, baseball is just a game. Some even find it boring. For others, it’s a way of life. It’s something that you’re born into and something that fills you with an indescribable sense of pride. For members of an Oakland youth baseball team, it was a way out of a less-than-desirable life.

The documentary film “Ghost Town to Havana” follows this baseball team from the tough Ghost Town neighborhood in Oakland as they learn the game and its lessons, which culminates into a trip to Havana, Cuba to play against another team.

The documentary, produced by local and Academy Award nominated filmmaker Eugene Corr and released in 2013, chronicles the struggle and frailty in the American inner city and makes the argument that sports, especially baseball, can be important in building character and improving lives.

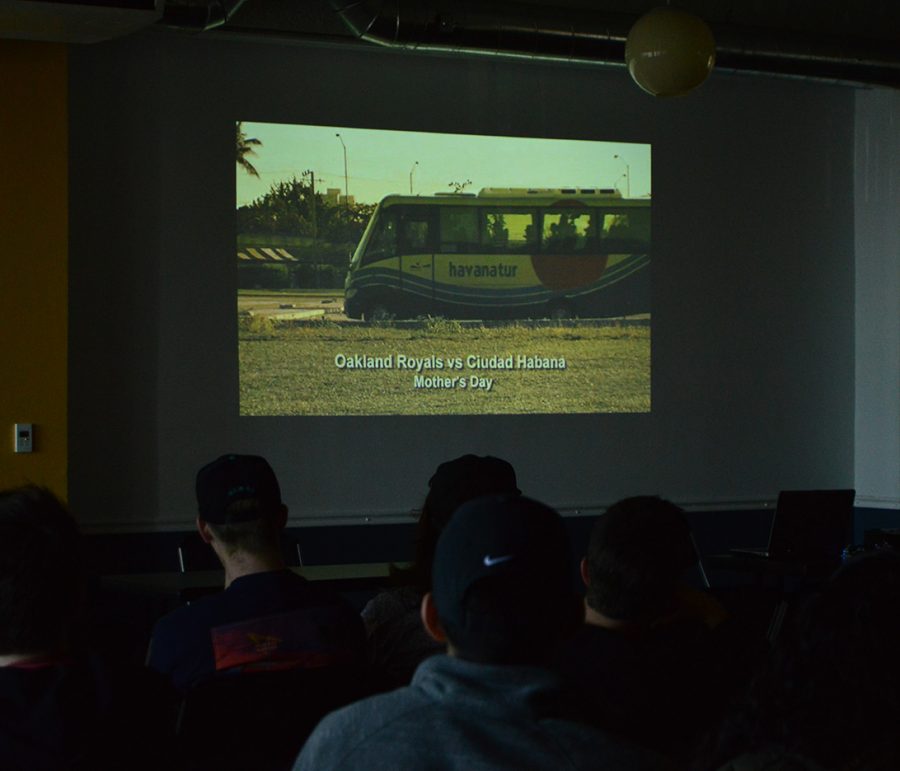

On March 2, Cal State East Bay welcomed Corr, a coach and player from the documentary for a screening of the film. The event was organized and hosted by history professor and baseball enthusiast Benjamin Klein in the Old University Union building at Cal State East Bay’s Hayward campus.

Corr’s love for baseball stems from his youth and watching his father coach college baseball in Richmond in the 1950s. His father coached at Contra Costa College and Corr grew up to play college baseball against his own father. He became inspired to make a film about baseball after visiting a baseball field in Havana during a trip to Cuba in 2007.

“I felt like it was a time warp, like I had walked back into Richmond, California in 1952,” Corr said. “The same level of skill, the same enthusiasm, the same racial mix and the same love and absolute love of the game.”

In Havana, he met a local mentor and baseball coach, Nicolas Reyes. His dedication to the kids he coached was unlike anything he had seen before. Reyes spent most of his time teaching children the game for almost no compensation while also caring for his own family and his wife who was in poor health. This led him to make a film about the impact of mentors like Reyes in baseball.

Corr soon came into contact with a coach in Oakland named Roscoe Bryant. Coach Roscoe, as many call him, put together the baseball team in 2005 in response to the shooting death of a boy in front of his house. With nothing but baseball equipment from flea markets and motivation, Bryant founded the Oakland Royals youth baseball team through the Cal Ripken/Babe Ruth baseball organization.

His goal was to teach the boys values that are hard to come by in a tough neighborhood. He called the team the “Royals” because he saw these children as the future kings and queens of their communities.

Seeing the similarities between Reyes and Bryant, Corr decided to document both coaches side by side. Corr introduced the two coaches through videotape and Bryant vowed to take his team from the Ghost Town neighborhood of Oakland to Havana, Cuba to play Reyes’ team.

When Bryant earned that sometimes up to three kids in Cuba would share one glove, he and the team decided to donate old equipment so that everyone of Reyes’ team could have their own glove and bat.

In 2011, when the Obama administration modified the travel policy to Cuba, it became possible for the Oakland Royals to make their trip to play Reyes’ team. The team arrived in Havana and encountered an entirely different culture and different style of living.

Baseball in Cuba is sometimes seen as a way out of the poverty and strife. A high volume of major league players come from Cuba where baseball is almost taught since birth. While both inner city areas like Ghost Town and Havana struggle economically, they differ in terms of family structure.

In Cuba, the family structure is different and in some ways stronger than what the boys from Ghost Town were used to. The film shows a family consisting of not just a mother and a father but also siblings and other extended family. In Cuba, children are cared for “impossibly well.”

The documentary explains how in inner cities, one or sometimes both parents are absent from the lives of their children. Children are often in many ways independent in their search of something to feel connected to.

Seeing the state of living in Cuba in contrast to the attitudes and happiness of the people gave the team a new perspective. “We take a lot of things for granted,” said Bryant. “Bottled water, toilet paper, soap. These are all items that we were hard-pressed to get while we were in Cuba.” Even though there was widespread poverty and a lack of basic needs, there was still a sense of positivity from the Cuban people.

“I was humbled because to see a culture of people with so little… they had the most positive outlook on life,” Bryant said. “The family structure was still intact, the way they loved, the way they played, the passion, was a beautiful refreshing thing for me.”

Rontral Acrement, one of the players who was on the Royals team and is now 17, attended the screening and talked about how his experience taught him the value of “having things.” He learned a lesson in what it means to need something versus want something. Acrement said that after the Cuba trip, he never asked for things he knew he didn’t need.

“I think it brought a sense of pride to our community first and foremost,” Bryant said when asked about the impact the trip had on him and the rest of the team. “It also opened the eyes of a lot of children.”

Sports can be so much more than just games. Before the trip, the Royals saw baseball just as something fun they got to do on weekends. After, they saw just how important it can be in a community like Havana which has baseball rooted in its culture.

The hope of Corr is that with leaders and mentors like Bryant and Reyes, kids can continue to be inspired to make positive changes in their communities whether or not it’s through sport. “If there were more Bryant and Reyes, the world would be a better place,” said Corr.