California cracks down on equal pay

October 22, 2015

It was 2004 when I first learned about gender inequality. I remember every 13-year-old sitting in that seventh grade history class in disbelief — outraged by the topic. No one could understand why in the 21st century men and women are still not treated equally. Towards the end of the discussion my teacher turned to the class and said, “Girls, regardless of what you do in this lifetime, your generation will still not make more than a man will.”

Eleven years later, a new California law has passed that attempts to eliminate the wage gap between men and women. It is the latest milestone in the century-old battle against gender-based wage discrimination.

In 2013, women working in the United States were typically paid just 78 percent of what men were paid, making the wage-gap 22 percent, according to the American Association of University Women. Senate Bill 358 (SB-358) is established to level out the wage-gap in California by allowing any employee who was previously fired, discriminated or retaliated against, to make a claim for reinstatement and reimbursement in any lost wages and work benefits. So if an employee feels like he or she is being paid less based on gender and the employer fails to follow up on the discrimination claims, they could be subjected to discrimination charges in the federal courts.

“The bill will do two things, one is it establishes substantially similar work as a standard for equal pay,” said Emily Murase, executive director of the San Francisco Department on the Status of Women. “Secondly, there are protections for employees to talk about their salary levels.”

On Oct. 6 at the Rosie the Riveter WWll Home Front in Richmond, Gov. Jerry Brown signed the California Fair Pay Act, which takes effect Jan. 1, 2016. The event truly belonged to the bill’s author, Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson, who told the crowd about the long journey in getting the bill passed. Jackson was elected to the state Senate in 2014, and is chair of the California Legislative Women’s Caucus.

Previous law prohibited employers from paying employees of the opposite sex less on jobs of equal work in the same working environment. This new bill prohibits employers from paying employees less for “substantially similar work,” regardless of their job titles, if they work at different sites and most importantly — gender.

The last time a law was enacted against wage discrimination was in 1963 when then president John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act, which also fought to eliminate gender-pay imbalance. Since then, San Francisco passed an equal pay ordinance in 2014, but this was only a citywide law.

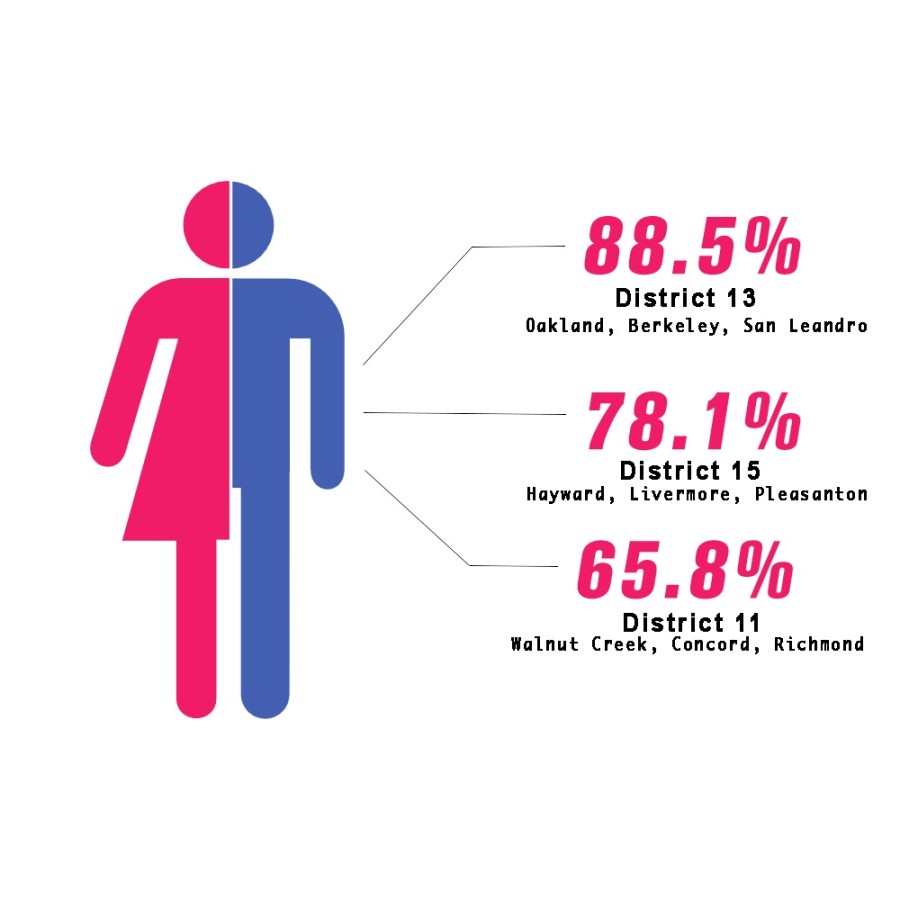

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, on average there is a gap of $10,762 between full time working men compared to full time working women. A 2014 AAUW report shows that in Hayward, males make an average of $70,589 compared to women who only make $55,150, meaning full-time working women only make 78.1 percent of what men make. The highest gender-based wage gap in California comes from District 17 which includes the cities of Fremont, Milpitas, Sunnyvale, Santa Clara, Newark, Cupertino and San Jose, also known as the Silicon Valley, where women only make 65.8 percent of what men make.

“The norm of secrecy has really disadvantaged people who were paid less than others,” Murase said. “Now the idea behind the law is to create an environment where it is okay to discuss pay, particularly when someone suspects that they’re being paid less than someone else, doing substantially similar work.”

She argues that the “norm of secrecy” is replaced by a workplace where it is okay to approach your employer about wage discrimination knowing that there is a law in place to protect you from being retaliated against.

Critics of the bill have argued that because of lawsuits, the law may lead to additional expenses for state businesses and California companies, which may force them to opt to move their operations elsewhere.

Labor law attorney and Lecture at the USC Gould School of Law, J. Al Latham Jr., explained to the LA Times that the new law will mean more employees taking more bosses to courts — which will lead to more litigation and thus could further weaken the business climate in California.

“California does not want companies that discriminate against women in pay or in any other way,” exclaimed Murase, which expressed not only the general sentiment of the law, but of the battle working women everywhere have tried fighting for ages.

Editor-in-Chief Shannon Stroud contributed to this story.