Is CSUEB earthquake safety a major issue?

September 2, 2015

Two 4.0 magnitude earthquakes shook the Hayward Fault Line in the last month, the first in Fremont and the latter in Piedmont. The 2.4 magnitude aftershock followed the first quake less than an hour later. Reports rolled in of items falling off of shelves, but no major damage was reported. The second quake hit on a hot, still day, similar to the 1989 Loma Prieta quake.

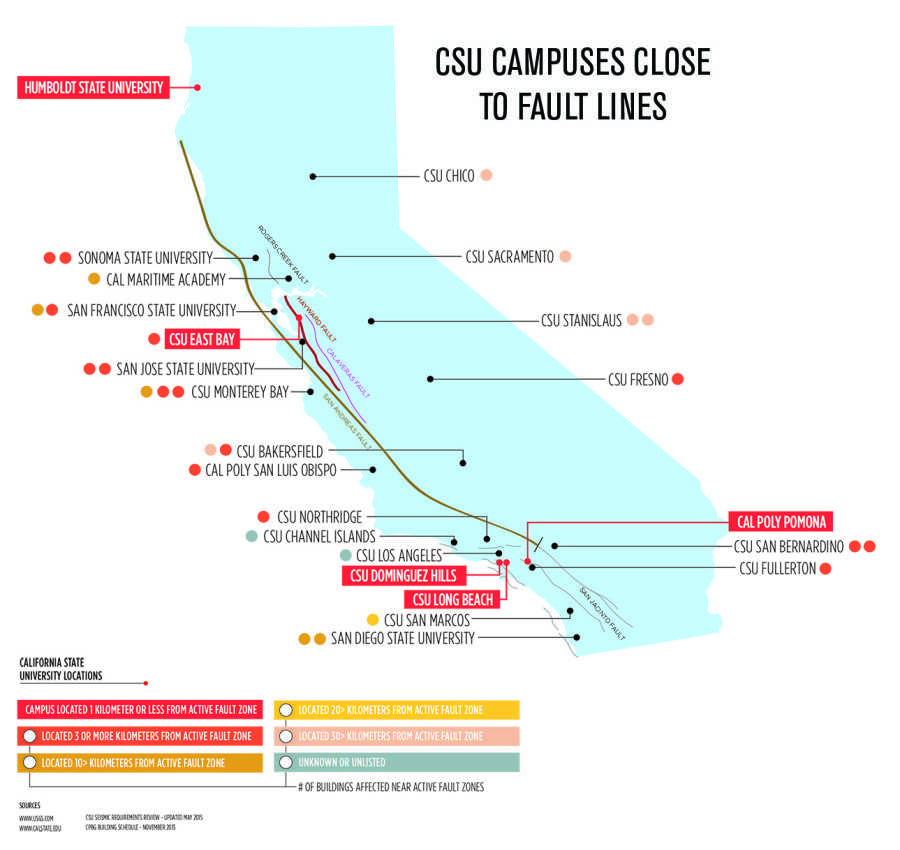

These recent incidents have once again brought earthquake safety to the forefront for a Bay Area community that has been told repeatedly that another big one is sure to hit. It’s of particular concern to many students at Cal State East Bay, a campus situated in close proximity to the Hayward Fault that is not adequately prepared for a major earthquake of magnitude 5 or above.

“To say that these earthquakes don’t mean anything is just not true,” CSUEB Geology professor Luther Strayer said. “While it isn’t necessarily a warning to a bigger earthquake, the movement still creates issues. Put your palms together and move them back and forth. The grooves in your hand get caught on each other and create friction, they don’t just slide freely. This is what happens when the rubbing of surfaces occurs. The bumps and surfaces have texture, they aren’t flat like mirrors so when they slide it creates the movement.”

According to the CSU Seismic Review Board, CSUEB’s Meiklejohn Hall is the least safe building in the entire 23-campus system in the event of a major earthquake. Meiklejohn was number two on the list up until Aug. 17, 2013 when the number one building on the list was demolished, CSUEB’s Warren Hall.

Both buildings were originally constructed less than one mile from the Hayward Fault, which according to Strayer and the United States Geological Survey is nearly due to produce a major earthquake in keeping with its average of every 140-150 years. The last quake on the Hayward Fault was a 6.8 magnitude that occurred 147 years ago on Oct. 21, 1868.

It’s a CSU-wide problem

In total, 28 CSU buildings could potentially collapse and 38 more would potentially risk lives in the event of a major earthquake, according to a list released by the CSU earlier this year.

CSU policy does not require the least safe buildings to be addressed for earthquake safety first. A panel of CSU officials decide the process and priority, however at the time of publication CSU had not confirmed how those officials are selected.

Despite ranking number one on the list of the least safe buildings, Meiklejohn Hall was not even ranked on the list of buildings to be retrofitted or demolished released by CSU officials in 2013.

In March the USGS updated its California earthquake forecast, which included the likelihood of an earthquake of 8.0 magnitude or more in California rising from 4.7 percent to seven percent.

“Previously we believed that faults acted on their own,” USGS Ned Field said. “We now know that activity on a fault can cause other faults to rupture. This information is why the likelihood rose so much.”

Field referred to the possibility of a quake on one fault triggering other faults to go off as well or the potential of multiple earthquakes going off at the same time.

“ShakeAlert” warning systems can help

The USGS gave nearly $4 million on July 30 to the California Institute of Technology, UC Berkeley, the University of Washington and the

University of Oregon for the production of “ShakeAlert”. “ShakeAlert” is an earthquake early warning system, which is designed to give people as much notice as possible of an earthquake through several mediums, specifically cell phones. The organization was granted $5 million earlier this year after making an appeal to Congress that was approved. If successful, the pilot program could spread to other local colleges where earthquake safety is a primary issue like CSUEB.

“ShakeAlert has the potential to save many lives,” Susan Garcia, USGS Earthquake Science Center representative said. “The warning system is designed to be faster than the seismic waves created by earthquakes. If a warning could reach the public in fault areas before the shaking begins, potentially thousands of people could be saved.”

CSUEB has an earthquake preparedness website with a video from 2009 but the link to Emergency Preparedness Information is temporarily unavailable. The school has an Emergency Operations Plan on its website that was revised in Sep. 2010. The 37-page document details the plan of action in the event of an emergency for the campus and surrounding community.

“I am old enough to remember the 1989 earthquake so I know how scary it can be,” CSUEB student Eric Nieves said. “I didn’t realize how close we are to the fault, I hope I’m not here when it happens.”

CSUEB’s Earth movement and Hayward Fault expert Strayer was instrumental in studying the Warren Hall demolition and the ripples the demolition created seismically. Strayer used seismic sensors to capture the waves and helped the USGS create a three-dimensional map of the Hayward Fault. The demolition was large enough to register on the machines used by Strayer.

“I can’t say they mean nothing,” Strayer said. “Small earthquakes lead to stress in a small area. For example, if you are in a crowd of people and you push all the people away, you feel better but how does everybody else feel? Small slips that occur put more and more load on the other parts holding on to the bumps and shapes on fault surfaces.”

Earthquake safety, a priority

According to the San Francisco Exploratorium, the taller a structure is the more flexible it is and the less energy is required to keep it from toppling during a seismic event. They further explain that because shorter buildings are stiffer than taller ones, a three-story apartment house is considered more vulnerable to earthquake damage than a 30-story building.

For buildings in fault zones, extra considerations must be taken into account when designing a building that is able to withstand a major earthquake. Materials such as wood and steel are preferred in fault zones because they have more give in a seismic event than stucco, concrete or masonry would, according to Garcia.

Jeff Bailey works for Bay Area Retrofit which was founded by Howard Cook in 1994 following the 6.7 magnitude earthquake centered in Northridge. Bailey said a lot of older buildings were constructed before many of the new codes around earthquake safety were put into place.

“An earthquake safe building means the structure can resist the force without too much damage,” Bailey said. “A certain ground acceleration measured as a g-force is what really affects structures. The new building codes tells us what we need to do in order to make structures withstand the force.”

One of the biggest ways to make buildings earthquake safe is to install base isolators, which isolate the base of the building from the earth’s movements which can be done two different ways. The first is by putting two smooth surfaces on top of one another under the building which will allow the surfaces to slide under the structure. The other way is by putting two structures on top of one another under the building that absorb each others energy and rock until the energy has passed through.

“We can’t guarantee there will be no damage,” Bailey said. “However constructing under the new codes can help. Look at the recent earthquakes in Japan. The new structures that followed the new code weren’t nearly as damaged as those old building that weren’t up to code.”

The most visible way that building designers are addressing the problem is by installing a truss. A truss is a wide base added to the top of the building that narrows and comes to a point, which according to the Association of Bay Area Governments, are designed to increase a building’s stability. The Transamerica Pyramid Center in San Francisco is one of the most visible examples of this technology in the Bay Area.

“The technology and the knowledge of how to construct buildings that can withstand an earthquake has come a long way,” Field said. “We now know how to make buildings safer, but no building could ever be considered earthquake proof, at least not now.”