Market Forces Driving the Fourth Pillar of Democracy

November 18, 2021

Media Bias, Misreporting, and Fake News: Real Reason Behind Our Polarized Society?

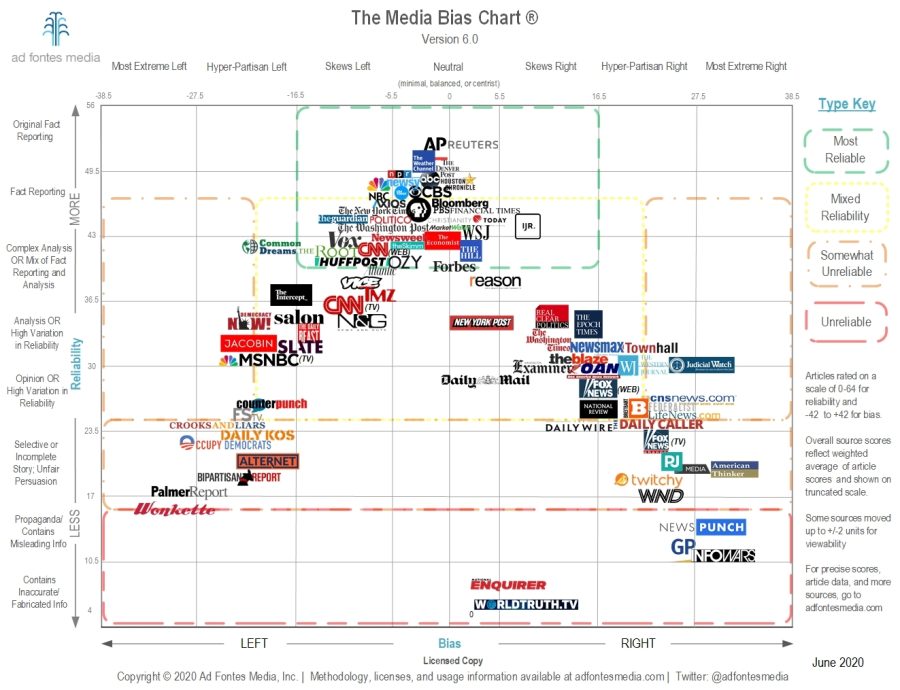

One of Trump’s most poignant legacies was the “fake news” campaign, wherein the former President derided the liberal bias present in news reporting and weaponized the alleged dishonesty rife within mainstream media. The message widely resonated with the public, continuing to reverberate in political discussions today.

Regardless of political leaning or individual attitudes towards Trump, a majority of Americans today are wary of news media partisanship and inaccurate reporting. Polled individuals believe that 62% of news originated or sourced from traditional media outlets (i.e., print media, television news, and radio) is biased, with 44% of news reporting from traditional media being perceived as inaccurate, a Gallup/Knight Foundation joint survey found.

While the issue of partisan journalism is multifaceted, the deregulation of media and the disruption by digitization are two of the most cited among them.

Deregulation of media resulted from a two-fold development: the revocation of the Fairness Doctrine and the institution of the 1996 Telecommunications Act. Under the Fairness Doctrine, broadcasters were mandated to present controversial issues by accommodating different stances. The Doctrine was repealed under the Reagan administration in 1987, motioned under the assumption that the doctrine impeded freedom of speech.

The passage of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 under the Clinton administration removed the regulatory barrier to enter the communications business and enabled the fusion of broadcasting and telecommunications markets in hopes of stimulating private competition for the sake of expedited deployment of network technologies.

“Clinton exacerbated the problem [and] allowed for the consolidation of media,” explained Dr. Nolan Higdon, Professor of History and Media Studies at California State University, East Bay and the author of “Anatomy of Fake News.”

According to Higdon, the standard frame for news coverage until the collapse of the USSR vested upon the “‘Us Vs. Them’ disposition during the Cold War, which was then altered to fit a ‘left-right’ narrative. Without proper regulation in place, the ‘Democratic and Republican Parties [were allowed] to buy up as much media as possible,’ leading to a proliferation of media “indoctrination camps.”

Local news broadcasts were especially sensitive to market fragmentation and corporate consolidation, contributing to gaps in local reporting and the displacement of journalists. “There are less places to work where you make a livable wage,” explained Higdon, continuing to add that despite the magnified wealth and influence of media corporations after the 1996 bill, “we know very little because [media giants] don’t report on weekends, small markets, or overseas.”

Traditional media, however, is on the decline, which Higdon attributes to the departure from fact-based journalism and daft business practices. “Legacy media destroyed its own reputation [on account of] poor business models, which sought to capture a small demographic of the audiences and maximize profits [instead of targeting a large audience],” said Higdon.

Via continuous appeals to partisan affiliation, the media industry has lost credibility, which Higdon equated a “loss of oxygen:” necessary for gaining public trust and maintaining audiences. Consequently, the digital space is threatening traditional media by enabling the development of independent journalism through crowdfunding, thus emulating the “muckraking tradition,” according to Higdon.

While digital journalism may amplify individual voices and allow for journalistic self-agency, the online space is perniciously susceptible to misinformation or data manipulation. Americans are most skeptical towards news distributed by social media and internet-based outlets, viewing 80% of all news found on social media as biased, with 64% of news reporting done on online platforms perceived as inaccurate.

Higdon elaborates that to rival traditional media; digital outlets may be tempted to sensationalize and be more inclined to assume a populist lean, whether left or right, meaning that the online space is not immune to hyperpartisanship, but may rather be encouraging of it, acting as “new tools to amplify fake news.”

Continuing to mature into a digital age, the public is unlikely to resist content pandering and challenge the illusion of free choice that comes with media consumption, while outlets — old and new — are likely to pursue the profitable approach of capitalizing upon fear. “Fear is a great engagement tool,” stated Dr. Grant Kien, Professor of Communication at CSUEB, specializing in new digital media and an author of “Communicating With Memes,” — continuing that tailored fear is being dispersed quicker than ever before, due to the ease of echo chamber facilitation.

In a critique of our media consumption culture, Kien noted that “[The public] holds the media idealistically as a pillar of democracy, but it is driven by market logic, the economics of the industry,” highlighting the precarity of partisan media as a prime indicator and determinant of our political attitudes.

In this day and age, “All a politician needs is to build a big enough voter base, [without needing to] govern for everyone,” said Kien. When prompted for a solution in reconciling the political rift, Higdon proposed breaking up and regulating big media monopolies along with social media companies to allow for the rehabilitation of local reporting while proposing an implementation of “charging data dividends to get rid of some financial power” of tech giants.

Kien and Higdon have also pinned the degradation of educational standards as a culprit for hyperpartisanship, with Kien asserting that “the fix [shouldn’t] just be technological, as we are trying to fix a qualitative problem with a technological solution.” To combat the root of the issue, both professors expressed support for the inclusion of media literacy and civics courses into the school curriculum.

While it may be effortless to dismiss another based on our political proclivities and prejudices, Higdon believes that it is polarization that ultimately undermines this “radical experiment where we all control the outcome,” hence it is within the best interest of the public to be factually informed and engage in cross discussion.