Education behind bars

June 13, 2019

California State University, East Bay professors teach inmates

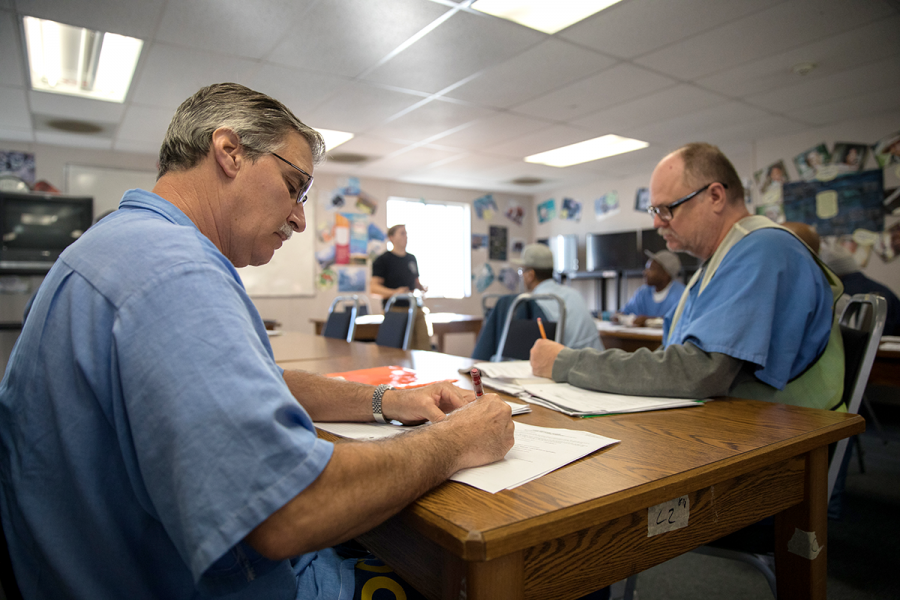

In a classroom that looks like any other in a typical university, men barely old enough to legally drink alcohol and others old enough to be their grandparents, fill the seats and share a burning passion for learning.

There are no computers or laptops and certainly no students distracted by the trivial temptations of a smartphone. Instead, these students, of various ethnicities, clad in oversized light blue buttoned-up shirts and blue jeans, learn the old fashioned way — by handwriting everything.

They come from all different walks of life, many rich with experience far greater than most university students.

Despite their vast differences among each other, they all share one thing in common: they are prison inmates and are determined to get the education they were denied or have regrettably neglected in their younger years.

These inmates, seeking higher learning whether to accomplish educational goals that they missed out on or prepare for life outside the penitentiary, are enrolled in San Quentin State Prison’s non-profit college program, the Prison University Project.

Since its launch in 2003, the Prison University Project has enrolled some 3,700 students, giving them the opportunity to earn an Associate’s of Arts degree, according to its webpage.

The program’s mission, according to its website, is to establish “standards and increase access to higher education in California’s prisons.”

“Everybody should have access to a college education because everybody counts. Everybody has value,” said Rashaan, who declined to provide his last name, a student from the program.

Additionally, they have about 300 students each semester while offering about 20 courses. In 2018, the average GPA for their graduating students was a 3.55, the project’s website says. The Prison University Project has received national attention and was even awarded the National Humanities Medal by former President Barack Obama on Sept. 16, 2016.

The program prides itself in having over 100 volunteer educators who teach inmates at San Quentin. Among those volunteers include California State University, East Bay’s Dr. Juleen Lam and Dr. Eileen Barrett.

Lam, an assistant professor in the Health Sciences Department who has taught at CSUEB since August 2018, has been teaching prison inmates at San Quentin Prison since 2015.

“I’ve been volunteering for a long time working with adult learners. People who are trying to go back and either get their GED, their associates or their bachelor’s degree,” Lam told The Pioneer.

Originally from the Bay Area, Lam briefly lived in Baltimore where she volunteered her teaching services, before moving back to the Bay Area in 2015.

“I actually read a news story in the San Francisco Chronicle when I was living in Baltimore about this program called the ‘Prison University Project’,” Lam said. “I just thought to myself, if I ever move back to the Bay Area, I’d like to get involved with this program.”

Lam mainly teaches general math and science courses at San Quentin’s university program.

Barrett, who has been a CSUEB faculty member for over 30 years teaching literature and composition courses, said her colleague, Dr. Douglas Taylor, who volunteered for the University Prison Project, recommended it to her.

Barrett has since enjoyed volunteering her hours and teaching English and composition courses to the San Quentin inmates, she told The Pioneer.

“[I want] to encourage them to reach their full potential as writers and better prepare them for writing and other college-level courses so that they can have an intellectually stimulating life,” Barrett added.

The Prison University Project has seen great success throughout its run, giving prison inmates a better outlook and direction in life. The program aims to reduce the number of re-offenders returning to prison.

Inmates who go back to prison for reoffending, also known as recidivism, is a very common occurrence in the United States. In 2005, the latest data examining prisoners released within 30 states in the US, over 67 percent of them were quickly arrested within a three-year timeframe, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

A similar trend reported in 2011 also found that seven out of 10 former inmates end up committing another crime and that half of them within three years will find themselves back in prison, according to the Institute for Higher Education Policy.

In a country where nearly 2.2 million American adults are incarcerated according to a 2018 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, many programs such as the Prison University Project have tasked itself with preventing recidivism.

Prison inmates who pursued education through the offered college programs were far less likely to go back to prison, according to a 2004 journal from the Journal of Correctional Education.

James S. Vacca, the author of the journal article and an instructor at New York State’s Great Meadow Correctional Facility college degree program, said he was able to witness firsthand how the education program for prison inmates was beneficial.

“Most of the inmates who graduated with four-year degrees from the college program provided by Skidmore College’s University Without Walls academic program in New York did not return to prison once they were released,” Vaca stated in his journal article.

Studies over the past two decades almost unanimously show that higher education prison programs lower recidivism in addition to lowering crime, “savings to taxpayers,” and “long-term contributions to the safety and well-being of the communities to which formerly incarcerated people return,” according to Harvard University’s Prison Studies Project.

While there are several other college programs that are similar, the Prison University Project is unique in that it does not charge their students a dime for tuition, supplies or books.

While it was founded in 2003, the program was based on a volunteer college program offered in San Quentin in 1996, said Jody Lewen, the Executive Director of the Prison University Project.

“[The college program] was started with no funding, an all-volunteer faculty, textbooks donated by publishers, and supplies scrounged together by the participants,” Lewen explained.

Two years prior to the creation of San Quentin’s former college program, Pell Grants for United States prison inmates were eliminated under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, also known as the Omnibus Crime Bill, according to Lewen.

Unlike San Quentin’s college program, prison educational programs throughout the United States require tuition. The Prison College Program provided by Adams State University in Colorado, for example, costs $220 per semester hour for courses.

Another similar program, offered by Ohio University, The Correctional Education Program, charges $340 per semester hour for incarcerated students who are Ohio residents while charging an extra $3 for non-residents.

Despite offering greater accessibility to inmates, San Quentin’s Prison University Project, in addition to the other similar higher learning programs for inmates across the nation, are generally considered a privilege that must be earned, according to Lam.

“It’s all the inmates with basically zero behavioral problems. If any inmate is caught doing something, the first thing that happens is they get kicked out of class and they’re not able to come anymore,” Lam stated.

Both Lam and Barrett said the teaching environment in San Quentin is mostly the same as in a typical university.

“Once you pass through all the guards and security, the physical classroom is not so different from our classrooms,” Barrett stated.

“It’s like any other classroom experience that I have at other universities. Even Cal State East Bay,” Lam said. “There are whiteboards, desks, students with books, binders, notebooks. I have a lecture. We do problems on the board [and] students have debates. It’s very much a typical classroom setting.”

Volunteer educators are safe within the prison, as there are several security protocols and the prison inmates who are offered into the program maintain good behavior, according to both Lam and Barrett.

“The guards were pretty serious and are more intimidating to me than the students,” Barrett added.

Security has not been a concern affecting any of the volunteers and both of the CSUEB professors have expressed having very positive experiences teaching at San Quentin.

“I’ve learned that they really had a passion for learning. They really wanted to do well,” Barrett said.

“I think it’s a great experience. At the Prison University Project, there’s a lot of flexibility. Basically, you can create your syllabus, you can decide if you have guest lecturers and you get to decide on your assignments,” Lam stated.