DHS silences the undocu-movement

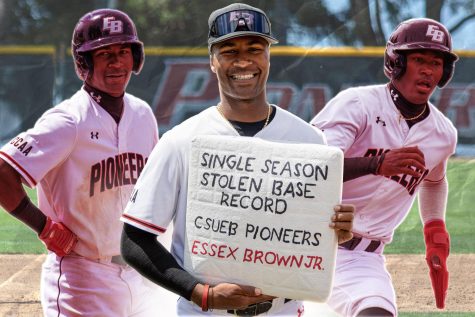

2015 redesigned Pioneer logo.

November 9, 2017

In response to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Privacy Act update, Rising Immigrant Scholars through Education (RISE), an immigrant student group at UC Berkeley, organized a “Cyber and Security Culture Workshop” on Oct. 23.

The air felt stuffy as more students trickled into the event. The seats curved along the walls and there wasn’t a single spot left untaken. One boy sat on the floor, laptop open and ready to take notes.

Valeria Suarez, one of the coaches for RISE, sat by the entrance, welcoming students as they entered the room.

Normally, there are only about 15 students that attend RISE’s weekly meetings. That day, there was around 30 in attendance. “During larger events like this, we get a lot more people,” Suarez said.

She introduced the presenters: a young woman wearing eyeglasses with her hair woven into a bun, and a young man with his hair slicked back, wearing a plain black shirt and jeans. They sat at one corner of the room, so that they were visible to everyone sitting against the wall.

The presentation was dense with information. They talked about all the different ways one’s information can be gathered online. Multiple technological platforms were introduced to combat this, which can be used to encrypt text messages, emails, browser history and other digital information.

This was a room full of young immigrant college students, but even so, they are targeted by the government because of that label: immigrant.

In accordance with the Privacy Act of 1974, DHS updated their system of records, which contains information pertaining to all immigrants that have entered the United States. The act allows the federal government to “collect, maintain, use, and disseminate individuals’ records.”

The Federal Register published the modified Privacy Act notice on their website, stating that publicly available information will be added as categories of the department’s records system. This includes “social media handles, aliases, associated identifiable information and search results.”

The information will also be utilized by US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to maintain border patrol, identify violators of immigration law and strengthen national security. In other words, social media accounts may be used to keep immigrants out of the country.

Since the 2015 terrorist attack in San Bernardino, members of congress argued for the need to check the social media information of Visa and asylum applicants as part of immigration processing. The attackers of the San Bernardino shooting exchanged private online messages that expressed their association with ISIS via social media.

During the Berkeley event, the move by DHS prompted many questions from the students in attendance.

“What are you going to achieve from [collecting our private information] when the people committing these crimes aren’t even immigrants?” said Danica Lacap, an attendee, referring to the recent Las Vegas shooting allegedly enacted by a 64-year-old American citizen. “It’s a way of discriminating against us, just finding an excuse to keep an eye on us.”

Lacap, 21, emigrated from the Philippines with her family when she was only five-years-old. She hasn’t been in her home country for 10 years and is now a naturalized American citizen. Despite being naturalized, Lacap is still subject to data collection.

Legal or not, the new ruling applies to every person that has entered the United States from a different country. It has created a distinct line differentiating a U.S.-born citizen from a naturalized citizen.

Gerardo Gomez, a DreamSF Fellow for Pangea Legal Services, raised another point of concern which involves immigrants’ extended community and support system. The modified system of records also targets associates of immigrants. The notice states they will include civil surgeon’s, law enforcement officers and interpreters in their data collection.

“The main purpose of that, in my belief, is for people seeking asylum or other immigration relief based on violence perpetuated against them,” Gomez said. “That’s the main way they get this immigration relief: proving they were harmed by American citizens.”

Gomez, along with 17 other undocumented youth, qualified for the DreamSF Fellowship hosted by the San Francisco Office of Civic Engagement and Immigrant Affairs (OCEIA). The fellows are engaged in immigrant advocacy through their work with non-profit organizations and they are informed of immigration-related policies and resources on a weekly basis.

Mayra Jaimes Pena, DreamSF Program Coordinator, found out about the new policy about a week before she had the fellows discuss it for their seminar.

“I firmly believe that ICE or different agencies have been observing and monitoring different community organizing groups,” Jaimes Pena said. “And this is a strategy to silence and immobilize those efforts that have been so successful.”

Since the rescindment of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in early September, immigrant rights activists are in an uproar over Trump administration move. Undocumented immigrants are speaking out about their status, advocating for DACA and the fight for immigration reform.

Yet with this issue concerning DHS, Bay Area community organizations have been silent. Isis Sykes, OCEIA’s Deputy Director of Policy, said that they haven’t done any action to advocate against the system of records update, especially since there are bigger immigration issues to focus on like DACA.

“Part of the issue is that there’s not much that anyone can do,” Sykes said. “It’s at the federal level and they’re directing federal people to do that.”

The fact that the notice was very lengthy and dense makes it difficult to comprehend how much of an imminent threat this is to immigrants. As Gomez mentioned, this issue is “slipping through the cracks.”

Despite the lack of advocacy work, RISE took the initiative to start the campaign “#DHSilences” immediately after the department’s policy was implemented on Oct.18. The following day, RISE uploaded black and white pictures of individuals with duct tape across their mouths that had “#DHSilences” or “#ICElies” written on it in black pen.

Suarez explained their plans to build the campaign by starting with social media. “I think that the point was to educate all immigrants on what is happening so that they’re careful and aware, but also to educate and mobilize all the so-called allies,” Suarez said.

The end goal is to reach out to the social media companies that are in the middle of the conflict between immigrants and DHS. Social media platforms can act as a barrier through their terms of agreement and privacy policies.

“I think Facebook, Twitter and Instagram needs to come forward and be like ‘look, you’re our customer, we respect your privacy, this is what we will let happen and this is what we won’t let happen,’” said Luis Quiroz, DreamSF Fellow. “I think that needs to be a demand, that we as users of these social sites and social platforms request.”