In-law units secret weapon to state housing crisis

October 19, 2016

In 2017, living in someone’s backyard in an in-law unit could become much more common, thanks to a new bill signed by Gov. Jerry Brown on Sept. 27.

The bill aims to ease some of the barriers and costs associated with building in-law or Accessory Dwelling Units and incentivize California homeowners to do so in an effort to combat California’s housing crisis.

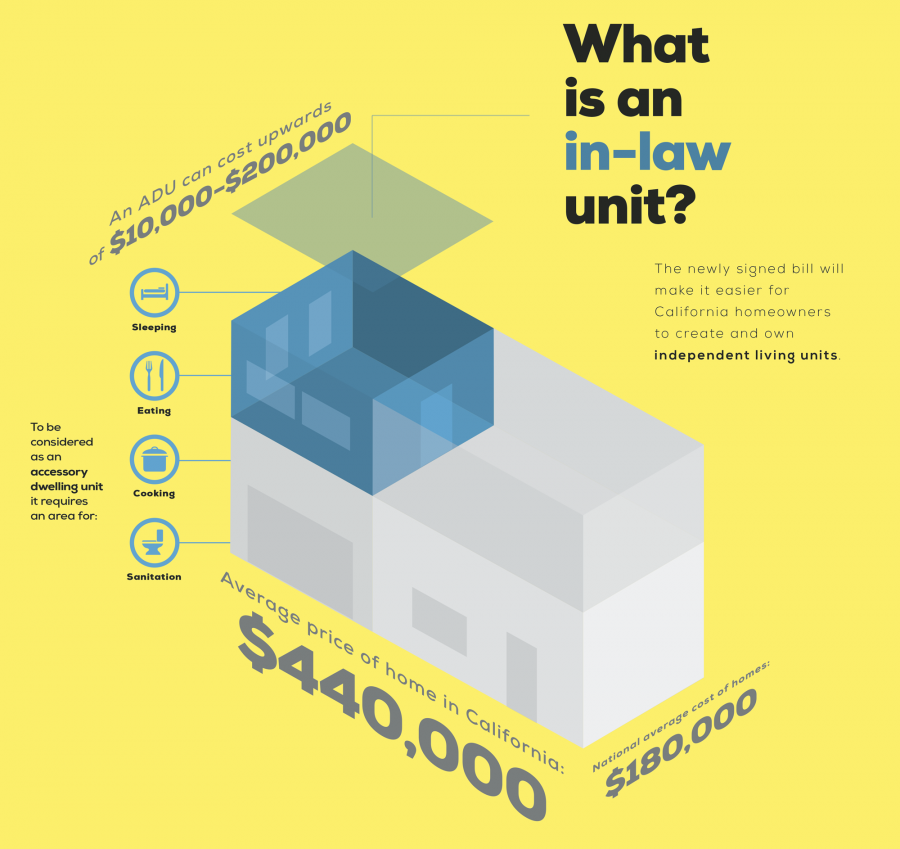

According to the legislature, an in-law unit is classified as “an attached or detached residential dwelling unit, which provides complete independent living facilities for one or more persons.” It is required to “include permanent provisions for living, sleeping, eating, cooking and sanitation on the same parcel as the single-family dwelling is situated.”

The bill, which will go into effect in Jan. 1, 2017, targets some of the strict requirements that discourage homeowners from constructing ADU’s such as parking and utility hook-ups. The bill will eliminate duplicate permits for water and electricity and removing the additional construction of fire sprinklers. It will also do away with the requirement that homeowners provide a parking space in specific instances — such as when the residence is located within a half mile of public transit, according to the legislature.

Rufus Jeffris, vice president of media, communications and major events for the Bay Area Council, a public policy organization that advocates for a strong economy and business environment in all Bay Area counties, told the Pioneer that the law would create more uniformity across the state. However, it doesn’t supercede every law that pertains to fees, permits and parking requirements that individual cities currently determine. Jeffris said that this is the first law that goes to this extent to amend ADU zoning laws.

Decades of housing shortages coupled with an influx of job growth in the Bay Area has contributed to a severe housing crisis in the Bay Area, said Jeffris.

This crisis is more than just policy, for many, including myself, it hits close to home. I live in a one-bedroom apartment that was built on the top of a four-bedroom house in Benicia. I have a separate entrance through the backyard and share a mailbox with my landlords, a young family with two elementary-aged kids. I do my laundry downstairs in the main house once a week and I pay just under $1,000 a month, which includes rent, utilities, trash and recycling services and high-speed Internet.

Right now, my living situation is ideal and virtually unheard of in here in the Bay Area, which is arguably the epicenter of the California housing crisis.

Senate Bill 1069 was authored by Sen. Bob Wieckowski, D-Fremont. The Bay Area Council sponsored the legislation and penned a letter to the governor on Sept. 1, urging him to sign the bill into law. The expansion of ADU’s across California, the council argued, is an innovative solution to a dire housing crisis.

San Francisco holds the record for highest housing costs in the country, averaging $3,500 a month, according to the Bay Area Council. The gap between California’s housing prices and the rest of the country has consistently been widening since 1970 and has risen from 30 percent above nationwide levels to over 80 percent. An average California home costs $440,000, while the national average price is $180,000. California rent is also two and a half times higher than the rest of the country at $1,240 per month, compared to $840, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office reported in a Mar. 17, 2015 study.

According to the legislature, California is not meeting current and future housing demand, which poses serious consequences for the state’s economy, greenhouse gas reduction goals and the wellbeing of California residents — specifically those who earn middle and lower incomes.

An ADU can cost tens of thousands of dollars to build, according to Jeffris, who estimates a range of $10,000 to $200,000. For all that, the increased area of an attached or detached ADU cannot exceed 50 percent of the existing living area, with a maximum increase of 1,200 square feet. However, the bill will significantly ease these costs for homeowners and create affordable housing for low-income single people and families.

There are about a million and a half homes in the Bay Area, estimated Jeffris. If just ten percent of people add ADU’s, there could be an influx of 150,000 new homes statewide. There is currently no method of tracking how many ADU’s exist in the state.

Jeffris said the lack of new construction of these units is largely due to a lack of political and local will to pass the necessary measures. “People want to keep things as they are, they don’t want to change,” he said. “That doesn’t mean we don’t have the responsibility to provide people across economic tiers with affordable housing.”

Opponents argue that a streamlined construction process bypasses a more thorough review process that takes all environmental impacts of a project into account per the California Environmental Quality Act, reports the Los Angeles Times. Some local governments have also criticised the bill because it centralizes the jurisdiction at a state level, rather than at a local one. Low-income families and young college students like myself, however, see it as an initiative that screams opportunity.

It’s been almost two years since I moved into my in-law unit. l work two jobs, 44 hours a week, but it still hits me every time I feed my paycheck to the never-ending stack of bills that I still wouldn’t be able to afford to live the way I do if I hadn’t found this hidden gem.

In-law units are a godsend and a strategic move — the secret weapon, if you will — in a battle to survive in the Bay Area.