Zimbabwean music soothes students

October 30, 2014

Moving his upper body back and forth as if he were in a rocking chair, he closes his eyes deep in concentration, sweating, and singing in his native language as he plays a song dear to his heart.

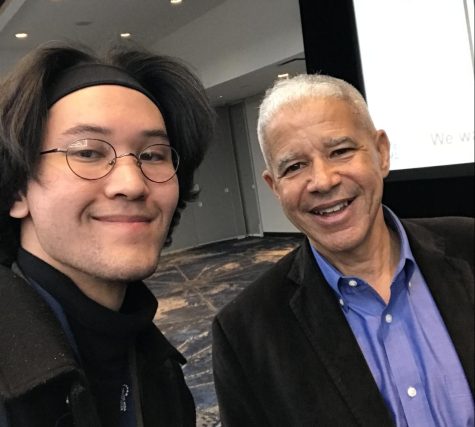

Cosmas Magaya, master mbira player and teacher, taught a class Wednesday afternoon, and also performed at CSUEB’s music building that same evening, as his four-month North American tour comes to an end.

Magaya is a senior performer of the mbira, a Zimbabwean thumb piano. His informal type of play is a craft that he has been practicing since the age of eight with a career that has spanned over five decades, according to Peter Marsh, assistant professor of music at CSUEB.

“You see me moving my body? That’s me dancing, inside,” Magaya said as the music came to a pause.

He played in front of a room that was a third of the way filled to capacity. Roughly 50 to 60 people made up the crowd. Some nodded their heads to keep pace with the songs, others danced from the comfort of their seat, and a few even fell asleep.

As Magaya entered the room in his cultural garment that included a brown cap shaped flat with the image of leopard skin and a loose hanging shirt with an opening through the neck, he received a warm reception from students, staff, and fans at the beginning of the performance.

Two others accompanied him throughout his recital; they were Tom Melkonian and Melissa Cara Rigoli, who are teachers and performers of Zimbabwean music.

Rigoli mostly stood barefooted behind Melkonian and Magaya as they sat in two of the three chairs that were facing the audience. She shouted numerous times and made a rattling sound with an instrument called the hosho that is used to accompany the mbira. Its sound is reminiscent of maracas; it is very sharp and adds a different dynamic to the performance.

The three artists sang together as if they were filling the soundless gaps whenever there was a silence in the room. There was a combination of high and low pitch sounds followed by yodeling. Songs as spanned between six to eight minutes. The transitions were smooth, indicating to the crowd that the song was over.

The mbira is a traditional instrument that is played by the Shona people of Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It is composed of three octaves metal keys that are mounted to a wooden soundboard that is played inside a large gourd, which includes buzzers to evoke a sound, according to Rigoli’s organization, the Santa Cruz Mbira.

Religious ceremonies known as biras, commonly use of the mbira. Strong players such as Magaya are said to have the ability to call on ancestral spirits, according to Kutsinhira Cultural Arts Center.

At the end of every song Magaya explained the themes of the songs briefly. His melodies included subjects like praying, determination, and inspiration.

“If you want to achieve what you want to achieve, go for it,” said Magaya of his song titled “Rhinoceros,” translated in English.

Throughout the performance, the mbira master told the audience that in Zimbabwe participation is encouraged and invited people to sing along and dance, although only a few did.

The soothing sound of the mbira accompanied by the hosho built a sense of relaxation and comfort. An overdose of such content, however, might send a person to bed sooner than expected.

The end of the performance was a shift in the way that the performers arranged themselves. The energy in the room heightened as all three played the mbira as they sat and simultaneously sang in various pitches.

“Everyone wants a good way of leaving,” said Magaya as he played the final song of the performance.