Former professor discusses overcoming being born with a cleft palate

March 20, 2014

Karl Schonborn remembers his first public humiliation as a young boy when his mother left him with a group of strangers. He tried to speak but the words that came out of his cleft-shaped mouth only sounded nasally, like a whining puppy waiting to be fed.

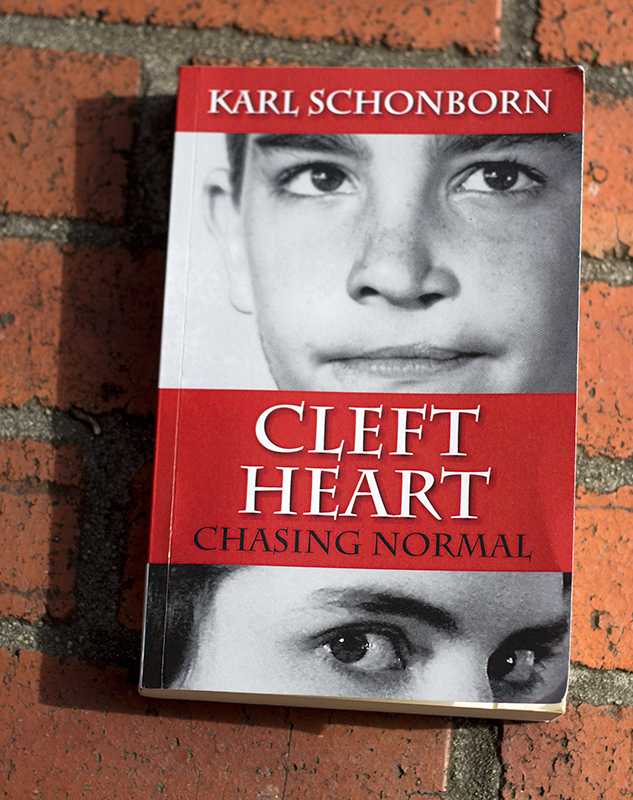

“Judgmental eyes and headshakes shamed me after I made a simple statement in front of the group,” Schonborn writes in his memoir “Cleft Heart: Chasing Normal,” published in August 2013. “A couple called me names I didn’t understand. Most turned their backs and left. I stared at the ground until mom reclaimed me…We both cried then.”

The retired California State University, East Bay sociology professor emeritus was born with a cleft palate, a fairly common birth defect affecting 1 in 600 children worldwide according to the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

“Instead of a mouth, I had a large triangular opening from my lower lip to my nose. I had no functioning upper lip,” Schonborn writes. “The gaping cleft in my gum and upper lip area pulled my left nostril to the side, flattening my nose. More importantly, the roof of my mouth appeared to be missing.”

Due to his birth defect, Schonborn faced a far from normal childhood. He said he was unable to cry as a baby and was unable to eat or suck on a bottle; so his mother had to force feed him using an eyedropper. When he became old enough to attend school in Palo Alto, Calif. he was unable to engage in activities with other children such as playing instruments and sports.

“Around the 5th or the 6th grade I had decided that sports were going to be my ticket to popularity,” Schonborn said. “If I couldn’t talk right, then I would just out run everybody. The doctors then immediately grounded me where they said the cleft is just one of many things wrong with me as a kid.”

“Around the 5th or the 6th grade I had decided that sports were going to be my ticket to popularity,” Schonborn said. “If I couldn’t talk right, then I would just out run everybody. The doctors then immediately grounded me where they said the cleft is just one of many things wrong with me as a kid.”

Schonborn later found out that aside from his facial abnormalities, he also had a heart defect which prohibited him from engaging in athletic activities. He then learned to express himself through visual things such as art and writing.

The book follows a suspenseful tale of a young boy who is bullied because of his facial deformation and speech defect; but fights back and chases his dream of living a normal life. He joins the debate team at Yale University, debating figures such as Secretary of State John Kerry, and then graduates and meets the woman of his dreams. The book comes to an unexpected close when Schonborn is faced with a family tragedy right before he is about to get married.

“[He provides] a poignant, heartfelt tale of endurance and hope,” wrote Kerry. “Schonborn’s story is an inspiration to all who endure physical or mental health challenges and those who care about them.”

Schonborn is only one of the many who has faced social stigmas due to his cleft palate. The first documented cleft lip surgery was in China around 390 BC on 18-year-old Wey Young-Chi, who would later become a soldier. The history of the cleft lip is based on a combination of religion, superstition and charlatanism, according to the Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery. Spartans and Romans would kill these children as they were considered to harbor evil spirits.

Today in developing countries such as Uganda, a child who is born with a cleft lip or palate is named ‘Ajok’ which means ‘Cursed by God,” according to cleft palate charity organization Smile Train.

The reason many cultures believed these superstitions about children with cleft palates is because they were unsure of what caused it. Today, doctors believe that clefts can be caused by “anything that might disrupt the normal processes of the womb in the mother between the fourth and 12th weeks of pregnancy, when the face and the palate is being formed,” said Dr. Ruban Ayala, MD, Senior Vice President of Medical Affairs for Operation Smile.

This can include things such as chewing tobacco, smoking, drinking alcohol or exposure to pesticides and pharmaceuticals the mother is taking. Clefts can also be caused by genetics. A mother or father can pass on genes causing clefting as either an isolated effect or as part of a syndrome that includes clefting as part of one of its signs.

Around the 19th century, the knowledge of surgical correction gave parents and children with clefts hope towards a normal life. Medical technology continues to improve to provide opportunities for those born with cleft palates.

Schonborn dedicates his life to sharing his story and aims to provide hope for children who are suffering from clefts, facial deformities or any type of bullying. He has studied the psychological aspects of facial differences as a social scientist and currently has a Facebook page and blog in which he shares information on how to deal with those differences.

“My hope in writing this is that every other pediatric surgeon will have a copy of it on his shelf and will loan it to parents or the kid he’s dealing with,” Schonborn said.

Schonborn also wrote the books “Violence and Conflict,” “Dealing with Society,” “To Keep the Peace,” and a screenplay “Stop, Look and Listen.”

He currently lives in Orinda, Calif. and visited Palo Alto High School for a book signing last Sunday. He will continue his tour for Cleft Heart: Chasing Normal May 29 at Columbia University’s bookstore and May 31 at Yale’s Barnes & Noble bookstore.